Hollywood’s collective idea of a great movie these days trends toward combining the wizardry of modern computers and animation with comic books. Caught between the strain of developing a complex storyline and knocking out another Batman movie, Batman wins every time. Since 1989, dark knight has been the focus of Batman (1989) Batman Returns (1992), Batman Forever (1995), Batman and Robin (1997), Batman Begins (2005), and The Dark Knight (2008). And perhaps if you thought telling, re-telling and re-re-telling the story was sufficiently exploitive of Hollywood’s creative juices and financial commitment, fear not, for in 2012, all eyes will turn to, you guessed it, The Dark Knight Rises. I would think by now we all get it, the flawed hero who saves us despite ourselves.

The result of all this redundancy is a movie industry that speaks ever more expensively to a steadily diminishing viewing audience who, like a 8 year old on a sugar high,, wants the same desert over and over and over. The beauty of cinema is forever lost in the cartoon effects of heroes stopping bullets in slow motion, cars that disassemble into warriors, people who kling like spiders to buildings, and spaceships that shoot laser beams.

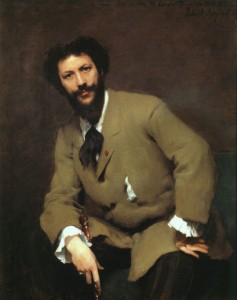

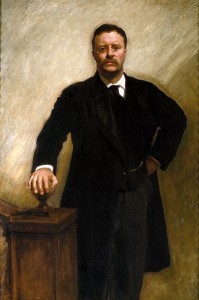

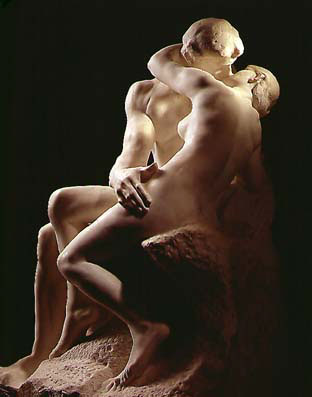

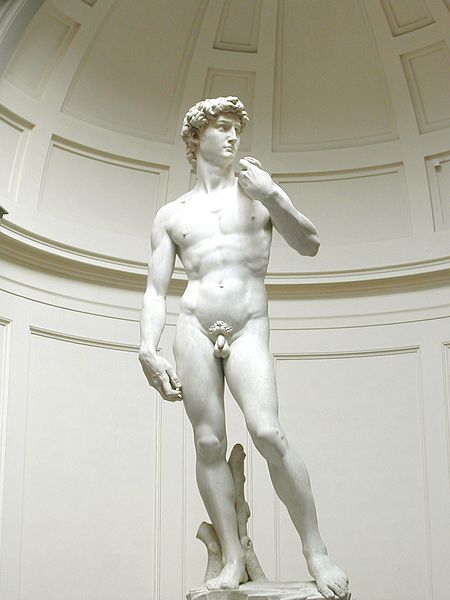

Enough with the laser beams. There was a time when cinema was considered an art , where complex emotions were explored through acting control, cinematography, music, and story in a perfect dance. The audience was captive to a primitive manipulation beyond their control, and transported in the dark to a world of inner fantasy, emotion, and depth of feeling that could change their very existence, and made gods out of the special talents that could elicit such moments. It was the time of the silent movie, with larger then life stars like Charles Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Lillian Gish, Charles Fairbanks, and Greta Garbo. It was the time of epic movies like Birth of A Nation, The Gold Rush, Metropolis, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Ben Hur. With limited technology and no sound, the artists had to take over, with emotions as large as the screen, lighting that increased tension, careful scripting that told the story through careful sentences, and direction that brought pace without the element of the spoken voice. Batman without sound or computers is better left to the cartoon book from which it came.

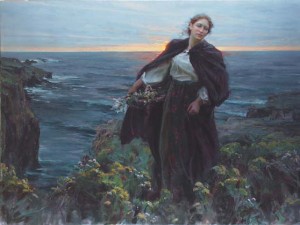

The cherished beauty of silent cinematic force is apparently not entirely a faint historical memory. According to excellent internet blog Libertas Film Magazine, a French film has made a heroic attempt to recapture the special nature of silent film, and is challenging audiences at the New York Film Festival to channel their deeper movie watching instincts and take on the challenge of a modern movie production told silently. Libertas reviews the film The Artist and is spellbound by the power of cinema to once again envelop the viewer in the artful beauty of silent screen. The story cleverly evokes the stress to a major silent screen actor, who must face the destruction of the art he knows with the coming of Talkies, and the relationship he has that bridges the two worlds. The story , the actors, and the moment come together according to Libertas in a special film that may prove award caliber and make all involved in the movie business re-visit the art form as it first presented in its most pristine evocation. I am looking forward to the opportunity to see this film, sit in the dark, and watch art unfold with the splendor of a time gone by. I suspect it will recall a depth rarely reached in this time of the superficial, and this era of acceptance for that which is easy and ephemeral, rather than that which is hard and oh, so lasting.