Public events sometimes exceed the real time shared experience to take on in retrospect a certain transcendent quality. As the event subsequently becomes elevated to an iconic cultural status, the number of people who actually were “there” and their memories of it, are exceeded by the ever larger group of people who over time tie the event so fundamentally to their life experience that they also become convinced they also were “there”. In our own life timelines, there are famous examples. “Woodstock” defined the sixties generation. The “Ice Bowl” mythologized the transcendence of a game into the very definition of Sport. The USA – USSR Olympic hockey upset almost overnight reversed the defeatist psyche of a world power and inexorably exposed the other from a veneer of irresistible force to one leading to eventual collapse. Events can define an era and announce a significant reordering of the traditional world into exciting, uncharted waters. December 22,1808 was such a night in Vienna of the Holy Roman Empire. The most amazing thing is almost anyone who was there to observe the kindling of a revolution had little idea that was exactly what just happened.

Ludwig Von Beethoven was born in Bonn, Germany in 1770 and for the first twenty years of his life gave little indication the massive talent that was to emerge. He showed sufficient musical ability to overcome the relatively mediocre instruction he received initially from family and instructors, soon to be”discovered” and gain notoriety from local regents due to his growing performance ability on the clavichord. He was supported to go to Vienna to perform and develop, the city standing then as the capital of music with Mozart and Haydn. He had superficial interactions with Mozart, but somewhat more intense “mentoring” from Haydn, who found him obstinate and difficult and assumed he would not have the discipline to take advantage his talents even Haydn could clearly appreciate present in the young man.

Neither Haydn or Mozart, nor any sovereign in Europe, could comprehend the power of Aufklarung, or Enlightenment, changing the relationship of the growing population of educated people and their leaders. The first matches went off in America, but the ultimate explosion was the overthrow of the oblige estates of France and the entry of a revolutionary governance. Beethoven was at the periphery but felt the rush of energy. He began to perform music with individuality and edge, and was more than aggressive in making sure no one took advantage of his increasing command of composition. At the time, composers had severe limitations in making a living and protecting their intellectual property. The incomes were often at the whim of benefactors, and performances, outside of some operatic theaters, were usually in salons of the wealthy. The idea of artist copyright and intellectual property was foreign to the 19th century at the time of Beethoven’s ascendance. Once the creation ended in the hands of a publisher, control over further publishing, or by whom, including preventing “adjustments” to scores, were gone for good. Attaching a public premiere of works orienting to their publishing was, in Beethoven’s mind, a level of control that would confirm unique capabilities, secure some much needed independent income, and forever put his stamp on how the music would be appreciated or compared to others. By arranging an ‘Akademie’ or public performance of his works alone, performed by him and conducted by him, there would be no doubt who was responsible for his genius and vision. The event was scheduled for December 22, 1808, at the Theater and Der Wien in Vienna, and Beethoven looked to change the very dynamic of a composer from one who entertains, to one who transcends time and culture.

A veritable revolution in music had been proclaimed with Beethoven’s massive Third Symphony, first performed in 1804. Standing the music world on its head with the size of the orchestra, the length of the piece, and the complexity of the structure, Beethoven further devised the concept of theme foundationally securing the entire piece. Avoiding both the entertaining and the sacred classically used to safely appeal to the royal elite, the Third thundered forward on the heroic of the individual. Individuality and power attained from ones own capacities was a revolutionary and dangerous prospect to the world order. Initially, Beethoven dedicated the symphony to “Bonaparte”, as he saw the initial triumphs of Napoleon representing the heroic zenith of the Enlightenment ideal, only to become disenchanted as Napoleon became a driver of conquest and dominance and declared himself Emperor. He renamed the symphony “Eroica” to preserve the revolutionary status, while not glorifying the darker reality. What the Eroica Symphony did more than anything else was close the door on the Classical Era in music and herald the birth of the Romantic.

Many composers have achieved greatness only to forever frustratingly attempt and fail to reproduce the magical uniqueness of the vision. Beethoven’s so called middle period of composition rewrote the book on musical genius. In the crowded years of the first decade of the nineteenth century, Beethoven’s prodigious creativity simply put out the mark that every OTHER composer to follow him would try to live up to. The Akademie performance on December 22, 1808, presented, among other pieces, the world premiere of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto, his Fifth and Sixth Symphonies and his Choral Fantasy, each a conceptual masterpiece that cemented Beethoven as the elite musical genius for all to compare. Two hundred and fourteen years later, the first three make or break any professional orchestra’s reputation and concert season. The fourth led eventually to th highest calling of symphonic expression, the Ninth Symphony and its Ode to Joy.

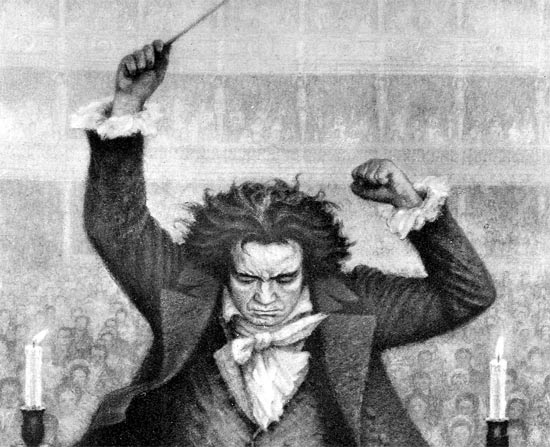

Typical for the times, neither the rapidly assembled orchestra for the Akademie performance nor its fiery and unforgiving, as well as progressively deaf, composer had any time or financial support for any serious review and rehearsal prior to performance. The night of the performance proved as confusing for the audience as well as the orchestra, as Beethoven himself drifted, jumped and bellowed in an effort to direct the performers through revolutionary music he could only hear in his head, and the performers could barely see on hastily scratched out scores barely illuminated in a dimly lit and unheated hall. Four and a half hours of complex, revolutionary musical creation took a back seat to confusion and downright audience exhaustion. Most reviews were derogatory. A few, however, recognized that what they had just witnessed could never be absorbed in one sitting, and the immensity of the achievements would declare itself over time.

The immensity of the achievements have declared themselves over time. Particularly the core three pieces changed music forever and will never grow old or fail to inspire.

The Fifth Symphony stands alone as the singular musical expression of classical music. The use of a motif, three short notes, followed by a longer note, “dadada daaah”, weaved brilliantly through four distinct movements, forever removed the need for a composition to express a creation upon a melody. Baser, human emotions and primordial forces, married by rhythm, propulse throughout and led future musicologists to define what Beethoven was expressing was “Fate, knocking on the Door”. It is unlikely that Beethoven himself felt the dot dot dot dash of the motif to be any specific realized expression of “Fate”, but he was clearly defining Struggle, Man’s inevitable battle, and eventual triumph, the core of his desire to reconcile the enlightened intellect and the forbidding romantic concept of the dark Unknowable.

The Fourth Piano Concerto may not be as accessible as the Fifth, but remains my favorite for its revolutionary character. There was little hint in Beethoven’s first three piano concertos that he was going to swerve so dramatically from the classical concerto relationship of the performer and the orchestra. Gone is the orchestra declaring the theme and the performer echoing and accompanying with synchronicity the alliance. Beethoven’s Fourth starts instead with the soloist individually projecting a tentative, dignified theme only to have the orchestra enter in another key and unrelated response. The two then joust through the first movement in unbalanced conversation reaching only at the very end a brief melodic truce. The second movement in five short minutes abandons all hope for unity. The soloist searches for dignity with greater and greater desperation, constantly interrupted by unfeeling orchestral demand for breaking of individuality, and imposed subservience. The clash grows until the soloist is left in a brief cadenza some of the most desperate, dissonant tones ever evoked prior to the twentieth century move away from tonality, and the listener is emptied and utterly exhausted – until Beethoven releases the suicidal tension and forgives, in the light Rondo conclusion. Some are disappointed in the conclusion , but Beethoven knew the emotion could not go lower without breaking the listener’s spirit forever, he had to turn away from the abyss. Expressed in the second movement, there may not be five greater minutes in music.

The Sixth Symphony was as far from the Fifth as one composer could possibly be while fulfilling the revolutionary whole. The Sixth, designed purposefully as an “impression” rather than a reproduction of a pastoral experience forecasted the massive nineteenth century conversion to the musical creation of imagery as tone poem. Scenery, brooks, sounds, and storms are not so much imitated as evoked. Beauty and nature as an experience is created with sound in a fashion that Bizet would attempt to emulate and Debussy would go beyond, but neither would exceed. As much as the Fifth would remove melodic constraint, the Sixth would inject musical color, and compositional rules were stretched and reoriented in such a fashion that the future composers feared challenging at the the risk of forever falling short.

The final piece, the Choral Fantasy, was hastily put together but was no less influential. Beethoven began to imagine the synthesis of composer, soloist, orchestra, and chorus into something greater than the coalescence and summation of its parts. The creative skeleton of olympian Ninth is there in its construct, and the eventual expressions of Wagner in leitmotif and “Gesamkunstwerk” or the total work of art. Beethoven knew what he was creating, but found the greater motif in the Ode to Joy to realize his vision 15 years later.

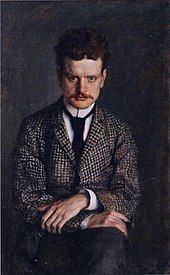

The three works, married to the vision of the fourth, performed in one sitting, left everyone else behind for good. Beethoven, in the shadow locally of Mozart and Haydn, was now the singular talent to which all other creative intellects would struggle to overcome. Sitting in Vienna, in the shadows of Beethoven’s immense accomplishment, left Franz Schubert to maintain his orchestral works in dresser drawers to avoid side to side comparison, leaving those magnificent creations to remain hidden until a later generation brought them to light. Composers subsequent to Beethoven feared ever putting forth a Ninth Symphony, to prevent their work defining composition being seen as a pale imitation.

Thankfully, Beethoven was never afraid of his own massive shadow, and continued to reach farther and farther out to the bounds of musical expression, despite becoming completely deaf and experiencing horrendous health challenges.

On the night of December 22, 1808, Beethoven put down his marker as one of humanity’s greatest creators, and each of those singular creations forever refresh our spirit and enrich us all.