What did you accomplish by your 24th birthday? Well, the pleasant little stone carving pictured above was the work of a young Italian from Caprese named Michelangelo, and it is worth reminding us all of this man’s brilliance and contribution to western civilization on the occasion of his birthday today. Michelangelo Buonarroti was born on March 6th, 1475, in the Tuscan nursery of one of the truly great explosions of man’s intellect and creativity, the Italian Renaissance. He was one of a line of spectacular talents that the beautiful rolling hills of the Tuscan countryside seemed to boundlessly produce, including Leonardo DaVinci, Ghirlandaio, Giotto, Duccio, Donatello, and Botticelli. Of this group of giants he was in particular, the Rock Star, a sculptor of immense talent and visions that could extract the most base human emotion and tension out of inert marble stone. His talents were recognized by his father early in life, and he managed to get young Michelangelo into the De’Medici school for artists in Florence, where he had access to the Medici’s great collection of Roman age sculpture and technical training from the sculptor Bertoldo Giovanni, but it was obvious to all that the student would soon be the teacher. The magnificent PIETA pictured above was Michelangelo’s early twenties coming out party, and he followed that masterpiece with the equally spectacular DAVID.  The intense sorrow of the Madonna for her dead son of the PIETA is transposed into the young male arrogance and aggression of the powerful DAVID, muscled, tensed, scanning the horizon for his opponent the giant Goliath, and convinced of the outcome of the titanic battle. These are not the emotionless immortals of Roman art. These are personal, entirely human subjects that are ageless not in their eternal youth, but in the universality of their human emotions and intellect.

The intense sorrow of the Madonna for her dead son of the PIETA is transposed into the young male arrogance and aggression of the powerful DAVID, muscled, tensed, scanning the horizon for his opponent the giant Goliath, and convinced of the outcome of the titanic battle. These are not the emotionless immortals of Roman art. These are personal, entirely human subjects that are ageless not in their eternal youth, but in the universality of their human emotions and intellect.

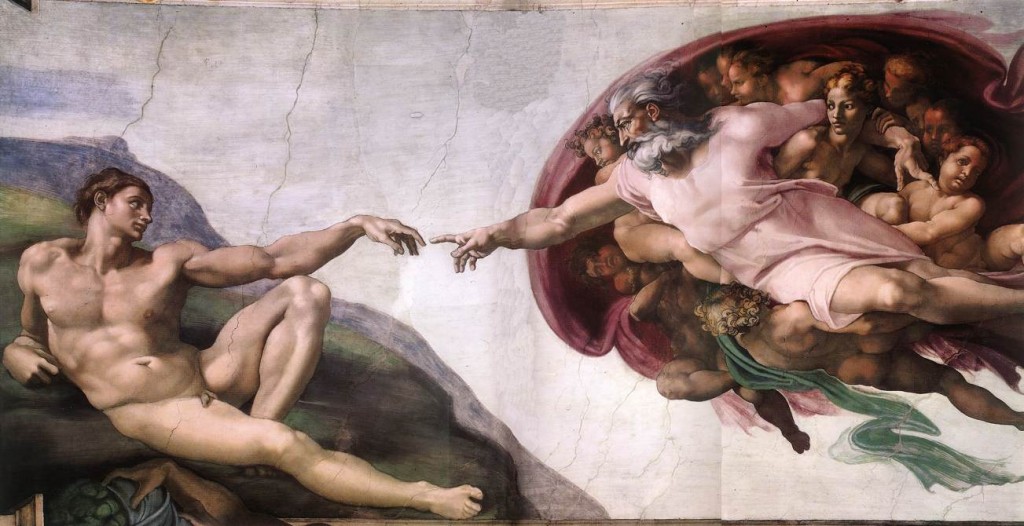

Michelangelo considered himself above all, a Rock Star, and never stopped in his words releasing the entrapped figures that were encased in stone, but he was not beyond showing his virtuosity in the artistic venue he thought least of, the art of painting. A sculptor of monuments needed a monumental scale for his painting expressions and found it in Pope Julius II’s commission to Michelangelo to the paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Asked to devise paintings of the 12 Apostles, Michelangelo lobbied and won the Pope’s permission to dramatically expand the scope to the story of Man’s Divine creation by God, the Downfall of Man, and the Promise of Salvation through the guidance of Christ. This huge fresco contained over 300 figures and nine episodes from the book of Genesis, culminating for the viewer in the spectacle of the CREATION OF ADAM , the critical spark of humanity, encompassing all its creativity, capability, and dark flaws, passed from the Creator to his creation with the recognition of free will passed between their eyes. The myths of the chapel ceiling suggest that Pope Julius in a perpetual battle with Michelangelo and his difficult personality, looked to the ceiling as a way of reining him in, by forcing him to express himself in the media he was least comfortable with, fresco, allowing for comparisons with his contemporary rival, Raphael. If the story is true, no one viewing the Sistine Chapel upon its completion had any doubt of the dominant figure in Renaissance artistic expression thereafter.

At a time when human free will and expression were under the oppressive dominance of a universal church and dictatorial overlords like the Medicis, artist of Michelangelo’s stature led surprisingly unencumbered existences. He lived life like he wanted, stated what was on his mind, and refused to work for patrons he felt would not allow him artistic freedom. A dangerous tact of life for most to take, Michelangelo’s genius appears to have been the unseen protector for him, as patrons clambered and competed for his time for project after project.

Michelangelo lived to the ripe old age of 88 when the average lifespan was in the forties, and remained prolific to his death. It is hard to view the Renaissance development without his pronounced imprint upon it. A man of his age, he was more a human for all ages, living the ideal of the human individual at a time when a individual life was unrecorded and unappreciated, and showed that the most valuable components of civilization were not its tyrant kings, but its individual talents and creativity. On the occasion of his 526th birthday, Ramparts of Civilization takes this moment to thank him for helping to make the world a better, more interesting place for the rest of us.