Fifty years ago today something new, brave, and wonderful occurred in the golden fields of Kazakhstan. Only 58 years after Orville and Wilbur Wright proved man could achieve controlled flight and resist the confining bonds of gravity in their 1903 achievement at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, a Russian hero proved forever that man could break those very gravitational bonds, and escape the confines of earth and find heaven. Despite the political overtones of the time, it is an achievement unsullied in its magnificence. Yuri Gagarin, a Russian test pilot, was propelled in a staged rocket into orbital flight, and became the first man to see the earth from beyond the blanketing atmosphere. The reality of manned light into space, long the stuff of science fiction and fantasy, became the very zenith of man’s capacity for greatness, and for a time made the then Soviet Union the center of science and technology in the civilized world.

The glorious achievement was the crowning accomplishment of a brilliant aerospace engineer named Sergei Korolyov, a man who had tasted the dark side of Stalinist Russia, when in experimenting with rocket flight, he was imprisoned for six years for “wasting” state funds in unsuccessful rocket experiments. With the German rocket success of World War II, Korolyov’s skill set proved too valuable for further abuse by the state and he was released at the end of the war to investigate German rocket technology and incorporate what he could into a Russian program.  The Americans managed the coup of rounding up the majority of Germany’s most successful rocket scientists including the young genius Werner Von Braun, and the initial lead in the concept of intercontinental rocket technology. Korolyov rapidly caught up and by the late 1950’s determined means of achieving multiple rocket engines harmonically delivering thrust in a single rocket, dramatically increasing payload lift capacity. In 1958, he stunned the world by sending a satellite into stable earth orbit with the launch of Sputnik, igniting a dramatic US effort to close the gap. The United States continued to formulate multiple options for rocket design, from the Atlas to the Vanguard and , finally the Jupiter, which would eventually be the successful and reproducible design. This continued multi-directed formulation resulted in occasional launch embarrassments and dead ends, resulting in a hesitation to take the leap to projecting man into space. The game was on, however, as the Russians placed a dog in space, the Americans a chimpanzee, and progressively more aggressive satellite weights were thrown into space. Korolyov saved what he knew would be overwhelming spectacle in leapfrogging these sub-orbital efforts with animals and went for broke, proposing man flight into space, having the man complete an orbit, and safely delivering him back to Earth. The gaps in what was known were huge – how would man tolerate weightlessness, could he be counted on to tolerate the enormous gravitational forces, could he live through the fiery atmospheric re-entry? Korolyov left little to chance regarding the knowns he could control and determined to preconfigure the mission and have the space traveler be a passive voyager, with the flight controlled by preset radio signals from home. He determined he would need a man for the job that would be brave but compliant, look and act the part of a hero, and he found his man in Gagarin.

The Americans managed the coup of rounding up the majority of Germany’s most successful rocket scientists including the young genius Werner Von Braun, and the initial lead in the concept of intercontinental rocket technology. Korolyov rapidly caught up and by the late 1950’s determined means of achieving multiple rocket engines harmonically delivering thrust in a single rocket, dramatically increasing payload lift capacity. In 1958, he stunned the world by sending a satellite into stable earth orbit with the launch of Sputnik, igniting a dramatic US effort to close the gap. The United States continued to formulate multiple options for rocket design, from the Atlas to the Vanguard and , finally the Jupiter, which would eventually be the successful and reproducible design. This continued multi-directed formulation resulted in occasional launch embarrassments and dead ends, resulting in a hesitation to take the leap to projecting man into space. The game was on, however, as the Russians placed a dog in space, the Americans a chimpanzee, and progressively more aggressive satellite weights were thrown into space. Korolyov saved what he knew would be overwhelming spectacle in leapfrogging these sub-orbital efforts with animals and went for broke, proposing man flight into space, having the man complete an orbit, and safely delivering him back to Earth. The gaps in what was known were huge – how would man tolerate weightlessness, could he be counted on to tolerate the enormous gravitational forces, could he live through the fiery atmospheric re-entry? Korolyov left little to chance regarding the knowns he could control and determined to preconfigure the mission and have the space traveler be a passive voyager, with the flight controlled by preset radio signals from home. He determined he would need a man for the job that would be brave but compliant, look and act the part of a hero, and he found his man in Gagarin.

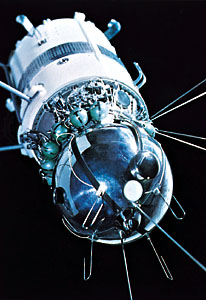

Yuri Gagarin was only 27 years old in 1961, but already a celebrated military pilot of the class of the Russian airforce the MIG-15, attentive, mathematically accomplished, and at only 5 feet 2 inches tall, perfect for the tight confines of the space capsule that would be his home in space. He was a member of the Sochi Six, an elite group of russian pilots selected to be the first to engage the cosmos, and on the fortnight before the flight, he was finally selected in a last second discision over Gherman Titov for the epic flight. Given the political circumstances of beating the Americans to the punch, the Vostok rocket was fitted for the manned flight after only two previous unmanned flights, and Gagarin was fully aware of the enormous risks involved.  On the morning of flight he was withdrawn and contemplative, and the weight of a potential dark outcome certainly weighed in his thoughts. In the best tradition of great pilots, he took his place without hesitation, and at about 0600 am at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, the Vostok rocket with a payload of 10,420 lbs and a solitary man was lifted into space. The capsule was projected into space into an oblong orbit that reached an ultimate height of 203 miles off the earth’s surface and in a little over 108 minutes, completed an earth orbit, and Gagarin became the first man to send a radio message from space, the first man to see the earth night fall from space, and the first man to experience a space emergency when a portion of his mechanized craft failed to separate from the re-entry vehicle, causing the craft to initially tumble wildly.

On the morning of flight he was withdrawn and contemplative, and the weight of a potential dark outcome certainly weighed in his thoughts. In the best tradition of great pilots, he took his place without hesitation, and at about 0600 am at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, the Vostok rocket with a payload of 10,420 lbs and a solitary man was lifted into space. The capsule was projected into space into an oblong orbit that reached an ultimate height of 203 miles off the earth’s surface and in a little over 108 minutes, completed an earth orbit, and Gagarin became the first man to send a radio message from space, the first man to see the earth night fall from space, and the first man to experience a space emergency when a portion of his mechanized craft failed to separate from the re-entry vehicle, causing the craft to initially tumble wildly.

The craft luckily separated from its undesired companion, and achieved stability just prior to re-entry. In a falsification propagated by the Soviets, Gagarin was reported to have landed with his craft, but Korolyov secretly had him eject from the craft at 23,000 feet and land by separate parachute, to attempt to assure a safe delivery of the human cargo on the very first manned flight. Gagarin and the Vostok 1 capsule landed separately, and safely, and the Soviet Union had a huge technological achievement and propaganda triumph. Gagarin was instantaneously a world hero, and his accomplishment significantly dulled the American response three weeks later, when Alan Shepard rode the Mercury space craft into a meager sub-earth trajectory and a brief 15 minute flight. Gagarin, through the brilliance of Sergei Korolyov, achieved what it would take the Americans another year to accomplish, true orbital space flight and safe return, a spectacular achievement that has not been dimmed one bit by the years of the subsequent American spectaculars.

The craft luckily separated from its undesired companion, and achieved stability just prior to re-entry. In a falsification propagated by the Soviets, Gagarin was reported to have landed with his craft, but Korolyov secretly had him eject from the craft at 23,000 feet and land by separate parachute, to attempt to assure a safe delivery of the human cargo on the very first manned flight. Gagarin and the Vostok 1 capsule landed separately, and safely, and the Soviet Union had a huge technological achievement and propaganda triumph. Gagarin was instantaneously a world hero, and his accomplishment significantly dulled the American response three weeks later, when Alan Shepard rode the Mercury space craft into a meager sub-earth trajectory and a brief 15 minute flight. Gagarin, through the brilliance of Sergei Korolyov, achieved what it would take the Americans another year to accomplish, true orbital space flight and safe return, a spectacular achievement that has not been dimmed one bit by the years of the subsequent American spectaculars.

Yuri Gagarin was a hero for the rest of his short life, and a profound influence on his time. He never was asked to pilot another spacecraft, considered too valuable to risk loss, yet ironically died in a MIG 15 plane crash in 1968 at the young age of 34. In that brief, shining moment fifty years ago today, he became the first space man, and turned the heavens and stars from the stuff made of dreams, into the reality of what man can do, when he puts his mind to it, and has the will to risk it all.

Just an FYI: First mammals to achieve orbit, in order: Dog, Guinea Pig, Mouse, Russian Human, Chimpanzee, American Human.