In the non-descript river town in south central England known as Stratford-on-Avon, in the last week of April, 1564, the modern English language was born. Prior to the event of birth occurring at John Shakespeare’s house at or about April 23rd, the language known as English had developed from the ground up on the backs of many influences. An initial germanic invasion of the Angles into the Northumbria region had impacted directly into the polyglot of dialects derived from the native Celtic and Saxon tribes and the 400 year influence of the Roman colonizers’ Latin creating a distinct language base known as Old English. Though not used as an administrative language, Old English found itself roots in literature most prominently displayed through the epic poem Beowulf. The invasion of the french Normans led by William the Conqueror in 1066 brought a ruling class of Gauls speaking predominently a French dialect, and the romance language inflection converted the pre-existing language of commonality into a new dialect known as Middle English. Its literature champion was Chaucer in the Canterbury Tales. To this point Britain was an island under constant threat of invasion and domination from warrior classes as diverse as the Germans, the Vikings, the Romans, and the Normans and each wave bent the language curve again and again, until it lay passive in wait for the spark that would create a distinctly English culture.

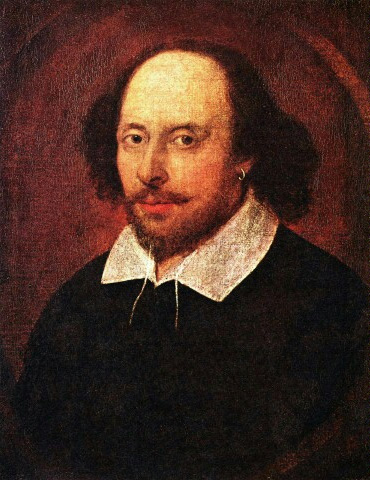

The spark required two pieces of kindle. The first was the Tudor queen Elisabeth I, who presided over Britain from 1558 until her death in 1603, marshaling in a permanently outward reflection of British influence through her defeat of the invading Spanish Armada in 1588, creating a British power progressively on par with continental powers, and assuring a unique English culture through her establishment of a state protestantism that evolved into the Church of England, and encouraging local dialects in administrative actions of the state. The second was the birth in Stratford-on-Avon of John Shakespeare’s son, William, who in his life of 52 years secured the language vehicle of modern English for all time as the language of art, poetry, history, and unity of a people.

The Bard of Avon was so spectacular in his talent for bring voice to a new, modern English that historians have fought for centuries as to whether a son of a glover and a farmer’s daughter, educated in local schools, could have possibly been the creative force behind the enormity of the masterwork he articulated. Shakespeare had basic grounding in grammar and the classics, but a keen ear for the lyrical tradition of the bard, the muse who memorized the ancient epic stories of ancient people who inhabited Albion and help create a distinct culture. He worked first as an actor with a local troop then as actor and playwright for an actor’s company, the King’s Men, at the Globe in London. His initial impact was not historical, but visceral, as the first mentions of Shakespeare in London are by “educated” critics who felt he was writing plays above his “station” in life.  Obviously the popularity of the plays was a driving force in getting elites to take notice. The very existence of criticism indicates a developing sense of a “right way and wrong way” to display a nation’s culture, the initial recognition of nationhood and national identity.at time when few were literate and printing presses few, the risk of Shakespeare’s brilliance to be swallowed whole by time was great, but thankfully, 8 years after his death, two compatriots of Shakespeare’s with his acting company achieved the publishing of all but two of his known works as the First Folio, and western civilization was given one of its all time creative jewels.

Obviously the popularity of the plays was a driving force in getting elites to take notice. The very existence of criticism indicates a developing sense of a “right way and wrong way” to display a nation’s culture, the initial recognition of nationhood and national identity.at time when few were literate and printing presses few, the risk of Shakespeare’s brilliance to be swallowed whole by time was great, but thankfully, 8 years after his death, two compatriots of Shakespeare’s with his acting company achieved the publishing of all but two of his known works as the First Folio, and western civilization was given one of its all time creative jewels.

A brief salute to the Bard on his birthday has no hope of forging a worthy dissertation of his genius. It is enough to say the English language and culture and its immense effect on western civilization was due in no small part by William Shakespeare’s gift for word and drama. His evolution from historical plays and poetic sonnets into the magisterial tragedies that created for the first time an audience’s window into the psychic and very human forces that drive thought and action have no cumulative equal in his language. From comedy to epic history to romance to tragedy, the unbroken line is of an ever more human voice that elevates and personifies life, death, and man’s own recognition of individuality. Over 400 years from their origin, the phrases and lyricism seem as fresh and meaningful today as upon their introduction to the English language. The words as expressed by Shakespeare forever cemented a reason for an English language and their universality explain much as to the dominance of English as a global language today.

On the 447th anniversary of the great Bard’s birth, let’s again celebrate the genius of his words, and one of the prime examples of western civilization’s greatest gifts to mankind, the freedom of the individual to develop his unique talents in his own unique voice, no matter his “station” in life.

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything

William Shakespeare – As You Like It

To be, or not to be: that is the question: Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep; No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to, 'tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish'd. To die, to sleep; To sleep: perchance to dream: ay, there's the rub; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause: there's the respect That makes calamity of so long life; For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, The oppressor's wrong, the proud man's contumely, The pangs of despised love, the law's delay, The insolence of office and the spurns That patient merit of the unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscover'd country from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all; And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry, And lose the name of action. - Soft you now! The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins remember'd.William Shakespeare – Hamlet

Happy Birthday, Bard of Avon.