We are coming upon the tenth anniversary of the conflict loosely described as the War on Terror. In October, 2001, in response to the atrocity of 9/11 and its identification as the most spectacular component of an ongoing organized war by radical Islamic organizations on to the shores of America, the United States initiated combat operations in Afghanistan. The described aim of the war was to identify and destroy the elements of terror organizations and to decapitate their developing coordination with like-minded governments. As put forth by President George W. Bush, there would be no separation considered between the terrorists, and the governments that knowingly harbored them. An initial rapid success followed, with the collapse of the Taliban government and the elimination of Al Qaeda terrorist structure in Afghanistan. The critical leadership of the Taliban and Al Qaeda escaped, though, and the war took on the more extended aims and actions that typify the initiation of conflict when ever conflict occurs. The war advanced to remove the tyrant in Iraq. It required an unhealthy and unstable relationship with Pakistan, a nation torn in half by its desire to be a modern power, and a population that desires to respond to a more reactionary religiously inspired life dogma. It forced hastily gathered leagues of nations to form military coalitions in Iraq and Afghanistan, only to have the actual brunt of fighting absorbed by the very few, and the commitment of most to waver. At ten years, it has achieved identifiable triumphs with the destruction of the financial networks of Al Qaeda, overthrow of Hussein in Iraq and stabilization of a violent battleground, capture of the planner Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, and finally, the death of the original inspiration for the war against America, Osama Bin Laden. Yet it has additionally stirred the secondary effects of sustained conflict, the mutation of radical Islam into other fronts, the emerging position of Iran as a successor to radical instigation, the collapse of governmental structures in the arab world with unclear outcomes and progressive instability, and the ongoing perpetual effort to stabilize the unsolvable problem of Afghanistan.

America is uncomfortable with extended conflict. Its painful wars have tended to have definable ends – The 8 years of revolutionary war ending in the formation of the country, the brutal four years of the civil war ending slavery and preserving the union, the 5 years of global catastrophe known as World War II ending in complete destruction of totalitarian powers and the unrivalled position of America as the economic and military colossus. Even the Vietnam War, identified as America’s only “loss”, completed its circle in ten years, with America’s capacity for rapid success returning in 1991 in Kuwait. The persistently moving endgame, and the enormous cost in material, resources, and blood, cost one president his legacy and led to the election of another committed to the reversal of war directed activities. The candidate Obama railed against the primary components of the war against terror. He promised the weary population of America the reversal of the war’s primary weapons in assuring the closure of military confinement of terror combatants at Guantanamo, the stopping of governmental privacy intrusion initiated by the Patriot Act, the removal of forces from Iraq, and the rapid stabilization through intense focus and commitment on the original incursion of the War on terror, Afghanistan. The realities of his position as leader of a warring country has resulted in him failing to achieve any of these stated promises. In fact, elements of perpetual war are setting in, with the realities of Afghanistan, the threat of Iran, and the expansion of war now on a wholly new and different set of principles to Libya. As a result, fatigue is developing in the country’s will that has finally begun to cross philosophical boundaries, and may have profound affects on the government’s capacity to sustain conflict. Politico reports a cross section of both Democrats and Republican representatives are beginning to question the very principles for continuing conflict from a common perspective. Their meeting of minds on the necessity for ending the conflict in Afghanistan bodes poorly for the President continuing to utilize the scenario of “cleaning up the mess” propagated by his political opponents as an acceptable foil for continuing war.

The conditions of perpetual war are comprehensively understood, and feared by those who study history. General Colin Powell, fully cognizant of the relatively recent national experience in Vietnam and fearful of historical precedents, defined a national defense posture for American involement in foreign conflicts. The Powell doctrine stated the components of a conflict involving America should meet the following criteria:

1. A threat to national security is present.

2. A clear objective is definable, and overwhelming force will be brought to bear to achieve swift conclusion.

3. The risks and costs have been fully vetted.

4. All other non-violent policy means have been exhausted.

5. A plausible exit strategy is in place.

6. The consequences of the action have been fully considered.

7. A broad international coalition is in place.

8. The action has the full support of the American people.

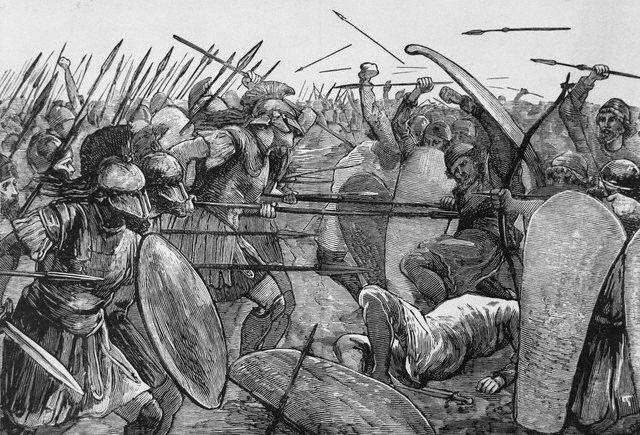

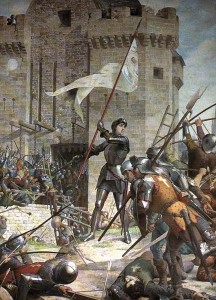

Powell feared perpetual war as a significant danger to a democracy. The elements of perpetual war include extension across political generations and regimes, the loss of original conflict intent, the conclusion of conflict not through victory but national exhaustion, and unpredictable outcomes that are contrary to the initial combatant’s goals. Two conflicts familiar to historians immediately come to mind. The Hundred Years War between England and France was fought across generations from 1337 to 1453. The origin of the conflict was a fight over who had the legitimate right to the crown of France. French Normans who had successfully conquered England in 1066 maintained ancestral ties to the French court, and through their rule of the provinces of Normandy, Anjou, and Aquitaine had control over more of France then the French king himself. When the French throne in 1337 opened without a viable heir, Edward III, king of England and linked to royal France through the Norman and Anjou provincial House of Plantagenet sought to enforce his right to the French crown. The house of Valois, the traditional line of French kings had a much different interpretation of history, and the battle was forced. Over generations and kings the war continued, to the staggering loss of half the French population and much of her wealth.  The presence of superior English battle tactics and crushing wins by Edward III at Crecy in 1346, the Black Prince at Poitiers in 1356, and Henry V at Agincort in 1415 in the long run did little to effect outcome, determined ultimately by the extended logistics required by the English and the vastly larger French population committed to the traditional House of Valois. Joan of Arc’s brief victory in 1429 at Orleans presaged the steady deterioration of the English position until, ultimately exhausted and over extended, the English were forced to give up their ancestral connections to the continent completely in 1453 and become an island nation only. The war, extended and so devastating, forced what was once a battle of knights and expensive armour, into a war of standing armies, tactics, economic damage, and nationalist rather than royalist objectives. The second example is the Thirty Years War, even more complex in its origins, extensive in its expansion, and devastating in its outcome to the continent. This war from 1618 to 1648, with origins in the protestant catholic schism of the 16th century,

The presence of superior English battle tactics and crushing wins by Edward III at Crecy in 1346, the Black Prince at Poitiers in 1356, and Henry V at Agincort in 1415 in the long run did little to effect outcome, determined ultimately by the extended logistics required by the English and the vastly larger French population committed to the traditional House of Valois. Joan of Arc’s brief victory in 1429 at Orleans presaged the steady deterioration of the English position until, ultimately exhausted and over extended, the English were forced to give up their ancestral connections to the continent completely in 1453 and become an island nation only. The war, extended and so devastating, forced what was once a battle of knights and expensive armour, into a war of standing armies, tactics, economic damage, and nationalist rather than royalist objectives. The second example is the Thirty Years War, even more complex in its origins, extensive in its expansion, and devastating in its outcome to the continent. This war from 1618 to 1648, with origins in the protestant catholic schism of the 16th century,  grew from local religious intolerances into a trans-continental struggle involving Spain, France, the germanic Holy Roman Empire, the Ottoman empire, the Dutch and the Danish, and the emerging protestant power of the north, Sweden. The religious origins became blurred and distorted, with Catholics forming coalitions with Protestants against Catholics, Protestants joining up with Muslims against Catholics, and Protestants fighting amongst themselves. The outcome over generations grew into the concept of nation states, ratified by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, that determined in its essence that catholics and protestants of a country would have to hold fealty to that country over their own religion. The expense of the conflict was a uniform devastation to the continental economy created by plundering armies and loss of working force, and death to 30 percent of the population of northern Europe.

grew from local religious intolerances into a trans-continental struggle involving Spain, France, the germanic Holy Roman Empire, the Ottoman empire, the Dutch and the Danish, and the emerging protestant power of the north, Sweden. The religious origins became blurred and distorted, with Catholics forming coalitions with Protestants against Catholics, Protestants joining up with Muslims against Catholics, and Protestants fighting amongst themselves. The outcome over generations grew into the concept of nation states, ratified by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, that determined in its essence that catholics and protestants of a country would have to hold fealty to that country over their own religion. The expense of the conflict was a uniform devastation to the continental economy created by plundering armies and loss of working force, and death to 30 percent of the population of northern Europe.

The process of perpetual war is well defined and reflects a steady drain on national resources, deterioration in national morale, and progressive loss of capacity for projection of power. At ten years, with no end in sight, the War on Terror deserves a studied discussion of the means of devolving a nation successfully from conflict, with goals achieved and national integrity intact. Victory is achievable when it is definable. Perpetual war is like a pathologic illness, where the perpetuation without victory, turns war into disease management, for an illness with no cure.