At one of the dioramas at the Wisconsin’s Veteran’s Museum in Madison, Wisconsin, stoic, tensed young men in black hats await orders to resist another surge of massed, charging Confederate soldiers in the hellish chaos of battle later referred to as The Cornfield at Antietam in 1862. They are young men comprised primarily of Wisconsin farmers and city laborers from the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Infantry Regiments and a similar group of men from the 19th Indiana, and later, 24th Michigan. They know what is about to befall them, and they are braced for what will surely test them to their core. The officer to the right is about to give the order to fire; a fallen comrade is at their feet to the left and will no longer respond. There is no doubt to the observer how these men will face their trial of fire, as they were already known by Antietam as a ferocious group of defenders that opponents preferred not to engage. They were recognized by their army 1858 issue Hardee black hats, that stood in contrast to the more contained kepis worn by other union infantry soldiers. They were known as the Iron Brigade of the West, and formed the steel backbone of union efforts from Bull Run to Appomattox through the entire breadth of the war. They are memorialized today, because these young farmers and laborers from the then new state of Wisconsin, in a war known for horrific sacrifice, sustained the greatest number of casualties by percentage of any maintained brigade in the war between the states. At Gettysburg alone the brigade lost 62%, or 1153 out of 1885 men, the 2nd Wisconsin 77%, the 24th Michigan an astounding 80%. What brought these unique men together to willfully sacrifice, and continually replenish their catastrophic losses with more of their sons and brothers, again and again, until victory’s relief at Appomattox, is the special calling of all who remembered on this special day of memory for the fallen, Memorial Day.

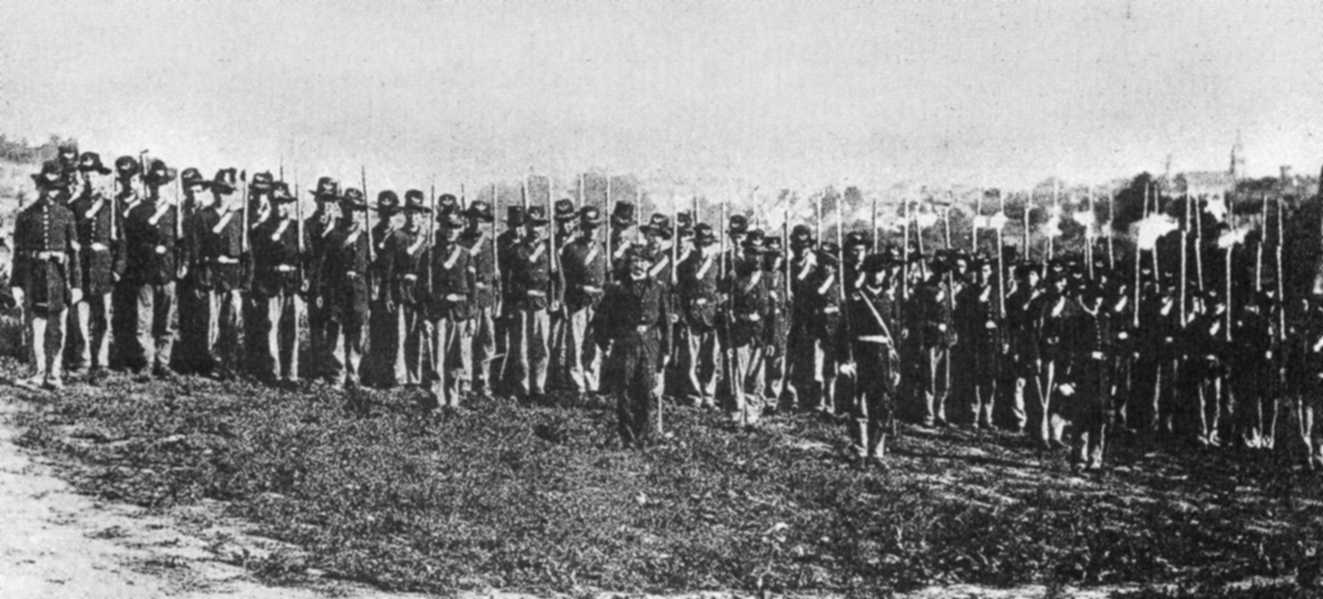

The call up in 1861 by President Lincoln for 75,000 90 day volunteers was especially perceived in the West. The new states of Iowa (1846), Wisconsin (1848), and Minnesota (1858) sought to show their commitment to the Union they had just joined and the importance they felt to the cause of free men. Governor Randall in Wisconsin had no trouble getting together volunteers. The regular Army of the United States in 1860 was a minuscule force of which over half the officers took allegiance to the their southern states over their union oath.  Therefore, an officer was essentially any man, other men were willing to follow. A prominent man could be a Captain if he could support the needs of 80 to 100 men under him, and get them to elect him Captain. A regiment consisted of ten companies and elected a Colonel, two regiments comprised a battalion, and four regiments constituted a brigade, led by a Brigadier General. The approximate 4000 men of the Wisconsin volunteers that started the war were initially led by Rufus King from Milwaukee, a part owner of the Milwaukee Sentinel and Gazette newspaper, appointed by Governor Randall to shepard the men into a fighting force. King had been a graduate of West Point in the 1830’s, and considered one of the state’s few men with any military experience, though it had been decades since he had resigned his commission. The training commenced at what would later be known as Camp Randall in Madison , the Brigade’s first action was with the Army of Virginia at the second Bull Run in August of 1862. General Rufus King, struggling with epilepsy, would not see battle, and was replaced by a succession of Generals that would obtain acclaim as leaders of this steadily more famous group, including Generals Gibbon, Meredith, Bragg, and Kellog. After Bull Run it was transferred into General Joseph Hooker’s First Corps, where it would enter Antietam in September, 1862, as First Brigade, First Division, First Corps, a position it would proudly hold until the end of the war.

Therefore, an officer was essentially any man, other men were willing to follow. A prominent man could be a Captain if he could support the needs of 80 to 100 men under him, and get them to elect him Captain. A regiment consisted of ten companies and elected a Colonel, two regiments comprised a battalion, and four regiments constituted a brigade, led by a Brigadier General. The approximate 4000 men of the Wisconsin volunteers that started the war were initially led by Rufus King from Milwaukee, a part owner of the Milwaukee Sentinel and Gazette newspaper, appointed by Governor Randall to shepard the men into a fighting force. King had been a graduate of West Point in the 1830’s, and considered one of the state’s few men with any military experience, though it had been decades since he had resigned his commission. The training commenced at what would later be known as Camp Randall in Madison , the Brigade’s first action was with the Army of Virginia at the second Bull Run in August of 1862. General Rufus King, struggling with epilepsy, would not see battle, and was replaced by a succession of Generals that would obtain acclaim as leaders of this steadily more famous group, including Generals Gibbon, Meredith, Bragg, and Kellog. After Bull Run it was transferred into General Joseph Hooker’s First Corps, where it would enter Antietam in September, 1862, as First Brigade, First Division, First Corps, a position it would proudly hold until the end of the war.

At Antietam, the southern commanders would experience the first real northern intransigence of the war as exemplified by the rock hard fighting displayed by the Wisconsin Brigade in the hell of the Cornfield in the single most casualty inflicted day in American military history. Stonewall Jackson wanted to know who it was in “those damned black hats” that proved impenetrable; the Union commander McClellan, surmised “they must be made of iron” and the Iron Brigade’s reputation was born. From Antietam, to Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and Overland, Richmond-Petersburg,and finally Appomattox, the black hats absorbed punishing blow after blow, yet unlike so many other regiments that disintegrated from the pressure of replenishing after onslaughts, continued to exist as a cornerstone of the Union infantry attack.

The battle at Gettysburg with its astounding losses of 70% casualty of the brigade secured its reputation for all time. General John Reynolds, desperate to attain the high ground on the first day of Gettysburg, until the bulk of the Union Army could arrive, sent the the Iron Brigade into the teeth of overwhelming numbers of Confederates entering the town from the north. The brigade repulsed the southerner’s attempts at achieving tactical advantage, and managed to decimate the Brigade of General Archer, capturing him and hundreds of other southern soldiers. The respite proved just enough to allow General Meade to secure the round tops at the gates of Gettysburg and force General Lee to impale himself upon the superior ground and ultimately lose the pivotal battle of the war. A single black hat, lanced with a bullet through its crown, (photo removed at request of museum) represents the courage, and sacrifice of that epic performance.

The cemeteries of Wisconsin are full of aging monuments to the over 12,000 fallen heroes of the brigade of young Wisconsin boys of that apocalyptic conflict, the names, and memories, progressively worn away by wind and time. These were young men, the sons of immigrants and immigrants themselves, that wanted to prove their worth to the nation as a whole, and were willing to sacrifice all for the ideal of the American dream. On this Memorial Day, the trumpets call out their mournful reveille for young men , from across the state, that wanted everyone to know they were an equal and essential part of the American Experience. There is no measure for personal sacrifice, no capacity to fully understand, what could drive such people to continue to defy the overwhelming odds, and serve, until the job was done, and the cause was secured. To all on this Memorial Day, thanks and prayers. On Wisconsin.

Hello, thank you for the great post on the Iron Brigade. The photo of the Black Hat is under copyright of the Wisconsin Veterans Museum and is not credited correctly. Could you please remove it or contact me regarding a photo release?