Its been over thirty years since I performed the daily grind of of getting up very early and taking the forty minute drive to my high school, but it was a drive I knew like the back of my hand, and could perform in my sleep. Every vista, every building, and every curve in the road from the hundreds of times I took the trip was thoroughly etched in my mind, or so I thought. When I took a little ride into my past a few years ago and tried the drive for old time’s sake, I found myself more than a little confused. In the thirty years that had passed, points of the road had in places not so subtly changed, buildings that were landmarks of the drive were replaced by other buildings, and my mind struggled to agree I was taking the same drive. When I reached my destination of the high school, it looked the same but did not feel the same, because the trip there did not feel as familiar, and the memory seemed somewhat out of place. Thirty years in the stretch of time is an eyeblink, but change affects memory and warps interpretation. When travel extends over hundreds even thousands of years, seeing the memory through the mists of time and the confusing layers of change is a daunting challenge.

I have found a travel writer that understands this problem and has some wonderful insights to help with both the joy of travel to ancient places and maximizing the experience. In her wonderful travel book, The Road from the Past – Traveling Through History in Franceauthor Ina Caro, wife of Pulitzer prize winning author historian Robert Caro has reworked effectively the problem of recognizing the significance of what you see on a trip. Acknowledging the logistics of most trips revolve around seeing everything there is to see due to the limited time available and the desire not to “miss” anything, Caro suggests a philosophical travel technique to improve your experience and memories of great venues. Ms.Caro looks at history as a wave, and recommends absorbing monuments, views, and venues in a chronologically appropriate historical perspective. Attempting to view the roman ruin, the medieval castle, and modern plaza in the space of the same trip distorts history and confuses the context of each. This beautiful little book focuses primarily on an arc of southern France to Paris, travelling specifically in a chronologically linear fashion, viewing the roman ruins, then the medieval castles, then the royal monuments and never intertwining them.

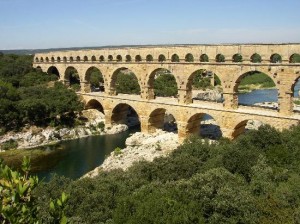

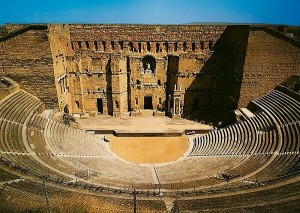

Suddenly the layers of confusion start to diminish as the road to the roman theater in Orange is linked to the aqueduct of Pont du Gard and to the Maison Caree’ temple in Nimes, and suddenly the 400 hundred years of Roman civilization and influence in Provence comes alive.

The wave of history then crests to Languedoc to Narbonne where the vestiges of roman citizenship was subsumed by the barbarian Visigoths and to the abbey of Fontfroide

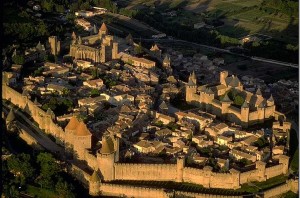

The wave of history then crests to Languedoc to Narbonne where the vestiges of roman citizenship was subsumed by the barbarian Visigoths and to the abbey of Fontfroide and the fortified city of

and the fortified city of

Carcassonne, where civilization clung in the dark ages against the marauding vikings. The wave then continues northwest to the valley of the Dordogne and a trip down the river to visualize the opposing castles of the English and French at Beynac and Castlenaud that epitimized the martial and feudal society of the devastating conflict known as the Hundred Years War.

Carcassonne, where civilization clung in the dark ages against the marauding vikings. The wave then continues northwest to the valley of the Dordogne and a trip down the river to visualize the opposing castles of the English and French at Beynac and Castlenaud that epitimized the martial and feudal society of the devastating conflict known as the Hundred Years War.  And then further north history pushes to the Loire valley where the preminence of royal lines begin to dominate and exploit their vast wealth with magnificient chateaus less for defense then a projection of prestige and power.

And then further north history pushes to the Loire valley where the preminence of royal lines begin to dominate and exploit their vast wealth with magnificient chateaus less for defense then a projection of prestige and power.

Ancient France comes alive under this treatment, and suddenly the clutter of historical layers is swept aside. The human emotions that attend seeing something in its context as did the occupants and travellers saw in that long ago time brings color and magic to ruins and views. The immense power and civilizing influence of the Roman world becomes a visceral sensation. The dark and foreboding fear of barbarian times is brought to perspective in the islands of security in a surrounding wilderness. The commitment of society to eternal war is projected through the martial architecture of every medieval turret. The vast power and overwhelming wealth of the royal line comes alive to the visitor at Chambord who feels the same awe as the commoner who could only look, never touch.

Ms. Caro’s little book is not a travelogue of places to stay, but rather a guidebook as to how to experience a place. It’s has already made my current morning drive just a little more interesting, and uncommon.