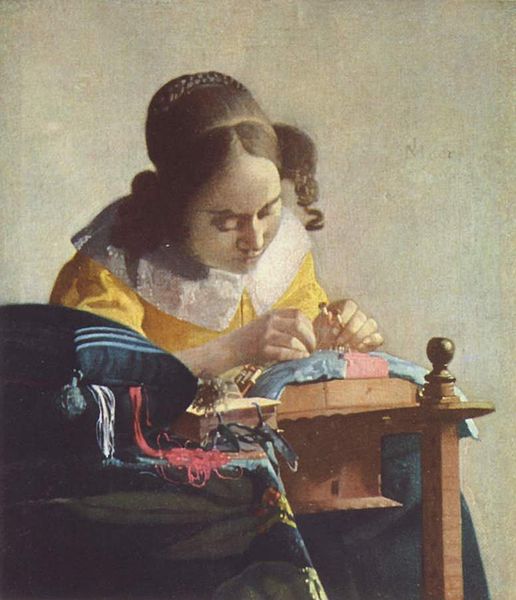

A relatively obscure local artist in his lifetime, whose entire known catalogue of artwork may encompass 36 paintings, has become an absolute modern superstar draw in any retrospective containing even one of his works. The Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge University in England is only the latest gallery to experience the enormous public passion and wonderment associated with Johannes Vermeer. A collection of paintings focused on women in domestic scenes in the Netherlands of the 17th century is crowned by four masterpieces of Vermeer including The Lacemaker pictured above, on loan from the Louvre in France. The tens of thousands that are crowding the exhibit are appreciating in person what most of us because of the minuscule opportunities to see Vermeer collections will never get to see – the chance to view several examples at once of one of the great creative geniuses of western civilization.

The most spectacular example of the Vermeer effect was the once in a lifetime 1995-1996 Washington DC National Gallery of Art exhibition of 21 of Vermeer’s 36 known paintings that resulted in miles long waiting lines and near hysteria for the artist that painted almost exclusively everyday people in repose before a window illuminated by daylight. Each rare Vermeer example of 17th century Dutch life encompasses a magic concoction of light, perspective, and composition that makes the simplest scene epic and immortal. The recognition of what was achieved by the man from Delft is the reason why Vermeer’s reputation in the world of art has grown to such immense status.

Johannes Vermeer was born on October 31, 1632, in Delft, Netherlands and lived his entire life of 43 years in the same city. His father owned an inn in the town square but was additionally known as a highly skilled silkweaver. The growing prosperity of the burgeoning middle class of craftsmen and businessmen in the Spanish Province Of the Netherlands led to a heightened interest in culture and with it art of Dutch artists. A true golden age of Dutch art including masters such as Rembrandt, Jan Lievens, and Frans Hals developed as wealthy patriotic men of the recently protestant Netherlands wished to view examples of Dutch culture and everyday life in their homes. Vermeer’s father recognized the opportunity and initiated an art dealership which his son eventually took on, becoming an outlet for his own work. It is not clear if Vermeer received specific instruction, but art had become an outlet for an explosion in cultural expression and the opportunities for numerous learning venues were probably available through his father’s business. His compositional style was what was popular at the time, genre and portraiture painting, placing people in their daily activities. But Johannes Vermeer was like no other of his time,though, in talent, though it would remain an obscure regional secret during his lifetime due to his extremely small output, and reality that essentially one benefactor, Pieter Van Ruijven, purchased the majority of his work, preventing dissemination. Vermeer, to his detriment during his lifetime, was a very slow, meticulous painter and constructionist, and at the height of his craft produced at the rate of two or three paintings a year.

But what creation. Vermeer managed to suspend time into an eternal vortex, taking waves of light and bouncing them in complex glows off walls, objects, and people that added immense definition and warmth to simple daylight illumination. The etherial effects of light elevated the subjects into a more sustained profound dignity of presence. The simple acts of pouring milk, sewing, or just quiet contemplation became in Vermeer’s paintings exemplary actions. Painting no longer had to be about heroic or religious subjects to be epic or spiritual. Living life and participating in its activities through Vermeer achieved a status once attributed only to saints and princes. It is impossible to view a Vermeer and not feel the simple pride and attraction to being human. Vermeer celebrated this richness of culture through the prolific and luxurious use of costly pigment paints, such as the very expensive ultramarine blue pigment made from lapus stone that dominates his painting color pallets, likely placing a significant financial burden on the family. The richness of color blasts through the natural light of the day, suffusing the subjects in an incomparable tonal warmth that few other artists have achieved. The symphony of color is perfectly accented by a spectacular understanding of light and shadow, that combined with Vermeer’s preternatural sense of composition draws the viewer into the perfect point of definition of each painting, a very modern sense of perspective at a time when the internal light was muted, interrupted only by the occasional candle. Not a single detail of the painting is ignored to create the sense of the whole, using everything in the painting to reflect upon everything else, resulting in works though small in size, worthy of hours of contemplation just to take it all in.

The use of expensive pigments, camara obscura for perspective, and meticulous, unhurried constructions reveal in Vermeer a self awareness of his talent. However economically damaging, his perfectionism did not allow a rushed product, and only those that are self aware would continually sacrifice their economic success for their personal satisfaction in achievement. The Dutch Republic, freeing itself of its Spanish overlords, found itself in constant conflict with its neighbors jealous of its upstart nature and economic vitality. The effect on the Dutch economy of constant conflict was suffocating and was particularly destructive to the resources needed to support a non-essential like art. Vermeer struggled mightily with debt, and the pressures of it may have led to his demise at 43. His tiny art output, however has had profound effect on the art world and secondarily on western culture itself. No one has ever managed to approach Vermeer’s achievement of portraying the act of being human as a condition of sacred, poetic beauty. Everybody who has ever gazed upon a Vermeer knows it in their heart.