“We must hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately. “ Benjamin Franklin at the signing of the Declaration of Independence July 4th, 1776

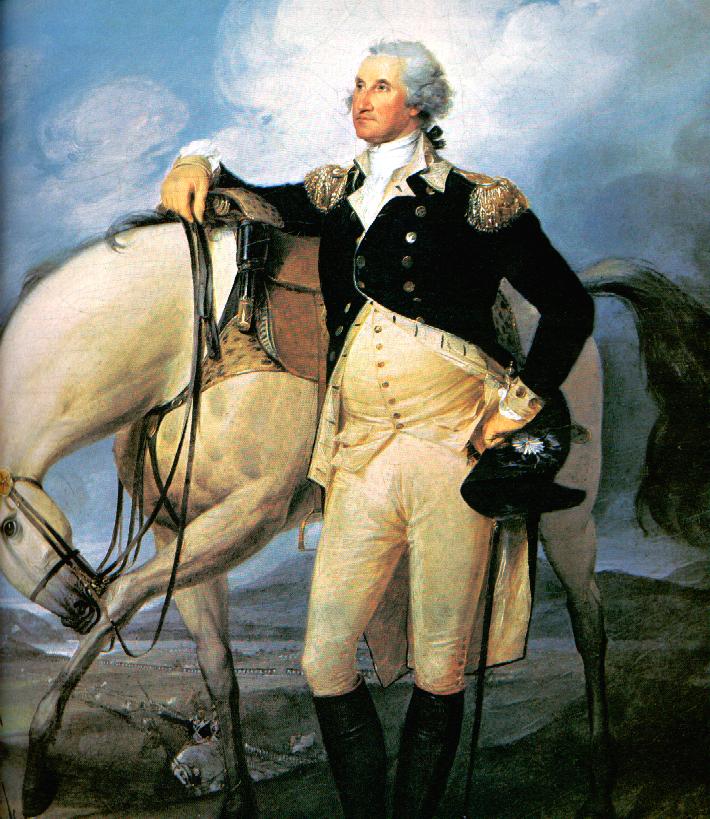

On the occasion of the 280th anniversary of the birth of George Washington, the above quotation locks in for all time the recognition of the inherent mettle of the man who has assumed the mantle of our greatest American. At the time of the declaration, George Washington was very likely the wealthiest man in the American colonies, owning massive swaths of Virginia, and a prodigious businessman. He was a key piece of Great Britain’s earlier strategy of defending land gains in the new world by fashioning leaders from the colonists, and had risen to colonel in His Majesty’s forces in earlier battles in the French and Indian War of the 1760’s. No process of political interaction by Britain would not include prominent Americans such as he, and the concept of representation for the common man would have not benefited him in the least. The wealthiest American, well thought of by his British cousins, a “noble” in a land of commoners , prominently potentially signed his life away on July 4th, 1776 on the altar of – principle. It is a concept so rare to today’s politician that the action viewed through the dim mirror of history still seems staggering. Benjamin Franklin voiced what all recognized, the claiming of the inherent right to separate, and thereby attaining for the American colonies all the land and resources of America formerly owned by Great Britain under the rule of a sovereign would be the greatest attempted seizure of all time, and would be intolerable for any ruler. Intolerable would equate with treason, a crime punishable by death, and no one would be more exposed to that charge than the leader of the rebellion’s armed forces.

What could George Washington possibly been thinking? He would have to raise a volunteer amateur army to defend the entire land mass of Atlantic facing America against the most powerful country on earth, with hundreds of times the resources, the world’s most powerful and well trained army and navy, and fully half of colonial America either apathetic or outright adversarial to his cause. It was the all confounding concept of principle that drew him inexorably to such a weak hand. Washington was born in an age where universal concepts of the rights of man and progressive exposure of the flaws of omnipotent rule were discussed as living entities. This was the Age of Enlightenment, where reason was considered the ultimate virtue, to be applied for the benefit and inevitable improvement of society. Emmanuel Kant the philosopher described Enlightenment as “Mankind’s final coming of age, the emancipation of human consciousness from an immature state of ignorance and error.” Utilizing reason was not the same as being realistic, or the immense challenge of an American separateness would have fallen upon deaf ears. Washington and others accepted ultimate risk as part of the price to pay for the right to reason. The principle of a thinking, mature individual to determine his own life course was too powerful to such men to allow the odds of attaining it in their own lifetimes the only consideration.

Principle drove Washington to stand to the front, and lead his ragtag army against overwhelming odds, through years of immense hardship, through tangles of wavering support at moments of crisis, through cataclysmic defeats and wobbly victories, to outlast the will of the powerful with the will of the reasoned. In 1781, after seven years of great personal sacrifice and enormous risks, Washington closed the trapdoor on the British army of Cornwallis at Yorktown, and with its surrender the British fife and drum played ” The World Turned Upside Down”.

It was indeed a world turned upside down, and the world waited to see the reaction of reasoned men to victory. What are strengths of principles when the ultimate power has been placed at the feet of an individual? The assumption of time immemorial was that to the victor goes the spoils, and Washington as head of the victorious force could have easily accepted the role of king as so many others over time had with a similar position. The rational man who fought for reason, however would have none of it, and the world stood amazed as the man who had fought for the right to achieve his own destiny, choose the destiny of a common farmer amongst men, his work done, resigning his commission of commanding general of the army.

The world had not seen a man like Washington, where principle ruled the man at the height of his powers. He would go on to serve his country again as its first elected leader, and upon completion of his service, again resign the reigns of power. No short tome can capture the depth of his personhood, and I suggest you look to two brilliant dealings with this uniquely American hero, Richard Brookhiser’s Founding Father and Ron Chernow’s Washington: A Life . You will find a very recognizable modern man in George Washington but one with immeasurable internal principled fortitude that seems almost alien to today’s American leaders. Where among us are the men or women that will accept the mantle of principle required to face down and rescue America from her ominous future? The answer will lie in someone who will live in the directed shadow of the American colossus George Washington, who accepted that in times of crisis, it is not importantly to succeed personally, but rather to succeed princibly. To the Marco Rubios and Paul Ryans of the world, the magnificent far off example before you is the roadmap to the ultimate triumph of a newly enlightened America.