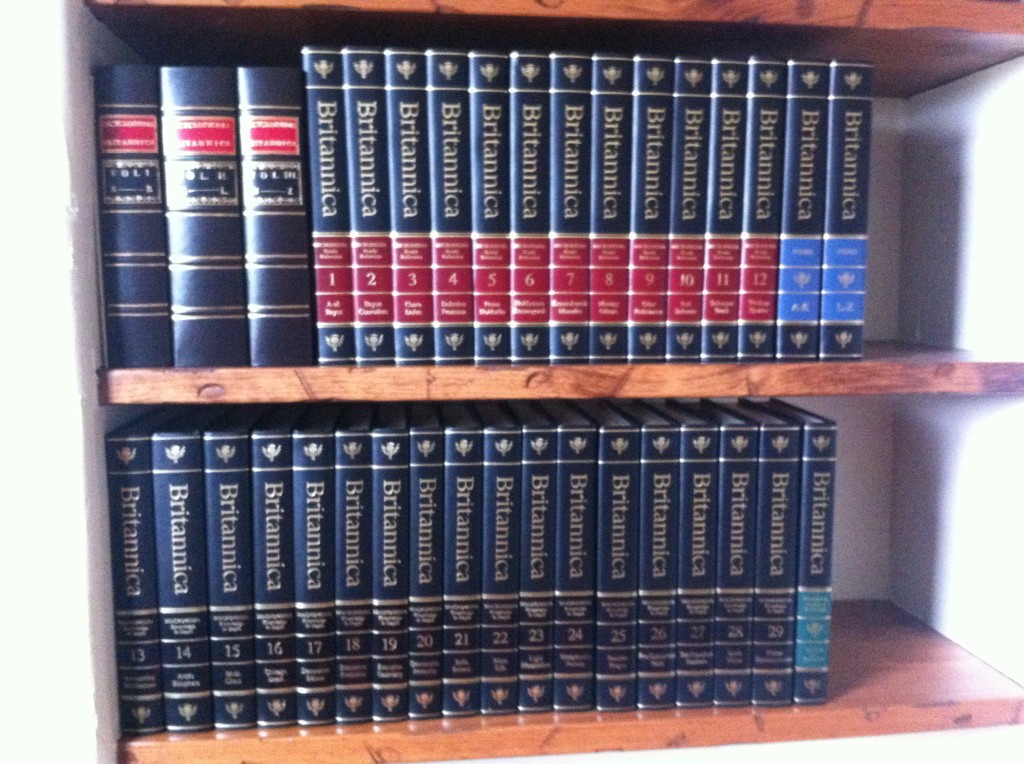

This past week saw a cultural changing of the guard in the defense of civilization’s ramparts. The Encyclopaedia Britannica company annouced that they would no longer produce a printed version of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and that the 2010 printing of the 15th edition would be the final one in book form. For 244 years, the Britannica stood as the undisputed reference champion as to the accumulated compendiumof man’s acknowledgement and understanding of the world around him. The first addition, published initially in 1768, by its Scottish founders Andrew Bell and Colin Macfarquhar, contained in three volumes a summary of the natural, historical, and physical world, with the intent to be both scholarly and to educate. The three volumes were assembled by a single editor, William Smillie. The final 15th Edition, published in 2010, claimed the contributions of over 100 full time editors, and over 4400 contributors, including many of the greatest reviewers known to their field of interest. Over 40 million words and half a million topics comprise the final printed edition.

I of course had to own both.

The pull to personally own the editorial bookends of 244 years of academic effort to summarize in a reference, available to all, the available knowledge of the world was too great for a lover of books such as I. In physical value, maybe not so intelligent a purchase. The progressive demise of the printed book after all has been well underway before Britannica’s announcement, and nowhere more acutely realized then in the reference book. Placing on a shelf a significant investment that almost from the moment of placing the words on the printed page is already a dated set of facts is the inherent fatal flaw of dinosaurs such as Britannica. The spectacular, universal, and immediately current information now electronically available on the Internet has brought printed references to their knees. The amateur scholar of today leans on the enormous capacity of search engines such as Google and rapidly updated resources such as Wikipedia to focus his search for fact and underlying truth. The 2010 Britannica edition in-depth article focused on global warming is immediately obsolete as the facts that form its basis have since been called to question in the East Anglia scandal and contrary evidence since. Similar problems with the permanence of printed truth versus the flexibility of updatable electronic truth inevitably made resources such as Britannica, Compton’s, and World Book a progressively poorer investment for individual research and education.

Oh, but what a run. The Britannica brought to bear the great minds over the centuries to countless topics that every family could peruse at their leisure. To review economics with Milton Friedman, Astronomy with Carl Sagan, Relativity with Albert Einstein, or Heart Surgery with Michael DeBakey was the unique calling of Britannica. The exalted position of Britannica was cemented in 1901 with purchase and movement of the company to the United States, exposing the vaunted treatise to the wonders of market concepts. The Britannica publishers piggy-backed their book on the concept of door to door sales, and the Britannica rapidly became a status symbol and an indication of the desire for higher learning in many American homes. People now could know what the privileged few at universities were privy to, the vast expanses of civilization’s knowledge base limited only by the effort and energy required to sit down and read the Britannica. It became a status symbol to claim to have read the entire set, and some claimed to have read multiple editions. Whether it was the Aardvark or the Zeppelin that interested you, Encyclopedia Britannica was prepared to make you a learned student of the subject.

There is of course a certain arrogance to attempting to cover all that we know in a tolerable collection of words. Arguments over the decades of what was left out and what was left in Britannica were as much a part of the story as the facts within. And now, the obvious champion is the Internet, with millions of experts and intense and constant vetting of information. I am a proponent of the Internet and the magical quality it has to bring the freedom of ideas to the entire world, both the privileged and subjugated, in a way that a few volumes never could. Encyclopedia Britannica acknowledges this, and continues from now on in the more flexible digital form for its subscribers. The romance of the leather bound books with gold leaf, however, brought a stateliness that the egalitarian Internet can never hope to have, and I mourne its passing.

The ongoing progress of civilzation often requires we leave some cherished traditions and concepts behind, but with the purchase of the first, and the last, attempt to place on paper that which we want to know, I have allowed myself a few more decades of the wonderful experience of wondering, reaching, searching, and knowing in the pages of a book. I look to William Smillie the 1st Edition’s editor to remind us of the value of such actions, in all their glory:

Encyclopaedia Brittannica 1768, 1st Edition

Heaven

“literally signifies the expanse of the firmament, surrounding our earth, and extended every way to an immense distance.

Heaven is considered by Christian divines and philosophers, as a place in some remote part of infinite space, in which the omnipresent Deity is said to afford a nearer and more immediate view of himself and a more sensible manifestation of his glory, than in other parts of the universe. This is often called the empyrean, from that splendor with which it is supposed to be invested; and of this place the inspired writers give us the most noble and magnificient descriptions.”

Now, that’s Heaven.