In today’s culture of dependency, it is hard to remember a time not so long ago when a visionary idea no matter how difficult, time consuming, or potentially immensely risky, was seen as a genetic characteristic of our civilization. For thousands of years until the nineteenth century, the progressively discoverable world was available at the speed by which a man could walk or run, or horse could be ridden, or a sail could push a boat by a fickle wind or current. A world so vast, that a day’s voyage could be arduous simply within the limits of a man’s sight, and the idea that one could know the world through personal experience seemed beyond the scope of a man’s lifetime.

Yet, there seemed to be no shortage of individuals that would take on seemingly impossible and dangerous journeys to somehow reduce the globe to human conceptualization. The ancient Polynesians using rafts to turn the Pacific Ocean into a highway between settlements. Marco Polo traveling for twenty-four years and 15000 miles along the Silk Road to the Forbidden Kingdom and back, to document a civilization superior to his own and open up a trade revolution that changed his home forever. And 500 years ago, Ferdinand Magellan pointing his ships west rather than east to develop a sea route for trade that ended three years later as a 24000 mile voyage that circumnavigated the globe.

Especially poignant is Magellan, for he did not live to see the fruits of his great achievement, having died two-thirds upon the way of his massive voyage, massacred on a remote Philippine Island at the hands of an angry chieftain’s warriors who took umbrage at his desire to play favorites and Christianize those he preferentially selected. In fact, of the 230 or so intrepid voyagers who accompanied Magellan on his epic journey, only 18 managed to circumnavigate and three years later return safely to their point of departure in Spain. These explorers were however to make Magellan immortally famous in their careful records they took of the voyage, so meticulous that they determined they landed one day younger than the number of sunrises and sunsets that had been catalogued since they had left, the first humans to document time travel, associated with traveling against the world’s rotation.

Magellan achieved many identified firsts, but it was certainly not his intension to take the longest possible route to East Asia. He rather hoped for a shorter rout traveling west to east then was at that time required to sail around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean. His desire for potentially shortened sea routes led him to avoid the rumored foul weather and dangerous waters of Cape Horn, at the southernmost tip of South America, instead navigating and ultimately discovering the Straits of Magellan, at the northern most aspect of the Tierra del Fuego, thus cutting several hundred miles off the voyage compared to around the Cape Horn. Through the straights he named the new ocean he encountered the Pacific, or ‘peaceful’, for it’s apparently placid waters as compared to the tumultuous Atlantic. The short cut was nice, but the travel west from Atlantic to Pacific around south America still required an 8000 mile journey, and certainly represented no bargain for traders in regard to time or risk who wished to go to the East Indies or China.

You might wonder how all this Magellan business leads us to the Panama Canal. Well, I’m getting there. You see, Magellan was not the first to recognize the new ocean, the Pacific. That honor went to Vasco Balboa, who in 1513 crossed the Isthmus of Panama and became the first European to view the western Pacific, suggesting a path thousands of miles shorter than Magellan’s circuitous route. But nobody got efficiently rich transporting goods across scores of miles of mountainous jungle (at least until the Conquistadores discovered native slave labor) simply to reload then in a boat. No, fortunes were made filling the massive cargo hulls of sailing ships and bring the goods home in one watery trip, making even the thousands of extra miles of the Cape Horn trip more viable than cross country.

Balboa’s vision of a shortcut across the Isthmus travelled the centuries unrequited until the machine power of the nineteenth century began to make the idea of a canal more than a pipe dream. The Europeans were still the initial visionary force behind the dream of a canal and the French got the farthest, developing a canal company that beginning in 1881 spent the next nine years on a tragic and fruitless effort to tame the 48 miles of mountainous jungle that separated the two bodies of water. Nine years later, having lost 22,000 workers to tropical diseases such as yellow fever and malaria, and having sunk the investments of 800,000 French investors, the effort was abandoned.

The canal idea was not too big, however, for the bountiful new world republic to the north. Despite having connected the continent by rail in an equally spectacular engineering achievement, goods and services were infinitely too expensive to travel by rail from New York to San Francisco, taking instead the ultimately cheaper, but daunting sea trip around the Cape Horn that would take months. The United States, in the midst of a boundless can do spirit occasioned by becoming the world’s biggest economy at the beginning of the twentieth century, saw the opportunity of the canal, and the power that would go to the country who ran it, too valuable to not take up the epic challenge. The United States engaged in some very dubious politics, positioned itself as the overlord of the vision and never doubted for a minute its ability to get the job completed.

The final vision came in the form of Theodore Roosevelt, a president who saw the future of the United States as a world power, and focused the immense energy and economy of his country on the huge project. From 1904 to 1914, the United States through its Army Corps of Engineers ,spent some 8.6 billion dollars in today’s money, used some of the world’s

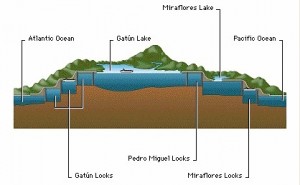

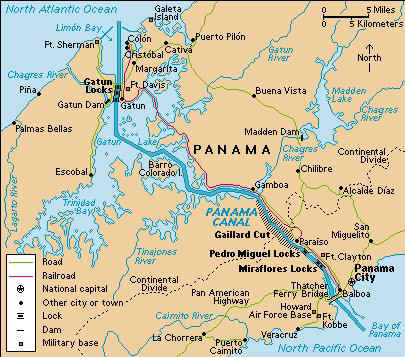

first bulldozers and earth movers to blast and sculpt its way through the Panama wilderness, moving over a 152 million cubic meters of excavated earth, losing 5600 workers to the same diseases that plagued the French, and creating the world’s most spectacular set of locks and dams that continue to function today in magnificent fashion. The locks still make possible for some of the biggest ships in the world to traverse huge quantities of goods from sea level up over the

mountains and back to sea level without ever unloading a crate off a ship. The 48 miles of beautiful locks and transporting tug trains make possible the movement of billions of dollars of goods across the Isthmus each year and reduced the epic path of Magellan from 800o miles to 48 miles and the time from months around South America to just 20 hours.

The nefarious politics that ultimately gave the United States the rights to build the canal and ultimately run the Canal Zone, and the just as uncomfortable politics that lead to the canal hesitatingly being turned over to Panama ultimately in 1999, can not take away from the incredible achievement that incredibly connected two oceans. The 150,000 dollar fee for traversing the canal is worth every penny for the ships filled with the hugely profitable trade goods that magnify Magellan’s dream a million times over.

August 14, 2014 was the 100 year anniversary of the opening of the canal, and the world has benefited greatly from the daring of a young nation that naively felt that it was chosen to do great things, and somehow got them done. It would do us well to remember the civilization we are so quick to blame for every inequity was once the natural spring of visionaries that conquered the Silk Road, circumnavigated the globe, made distance our servant, and took the impossible, and made it happen.