March, 1865

To reach beyond the mists of time and bring immediacy to the events that gripped a nation one hundred fifty years ago is an extremely difficult proposition. The war that cleaved across the breath of the American land mass and struck into the life blood of nearly every American family is at best a distant recollection and for most has little emotional relevance. The modern society struggles to understand the passion and commitment individual Americans brought to the concepts of union, liberty, individual rights, and the relationship of a governed people to its government that so stirred the nation to the cataclysmic conflict. From Sharpsburg, Maryland to Glorieta Pass, New Mexico, the remnants of titanic battle scattered among fields, cemeteries, memorials and roads the strategic value of which are known to few and passed by millions without a glint of recognition of what lies beneath the traveled path.

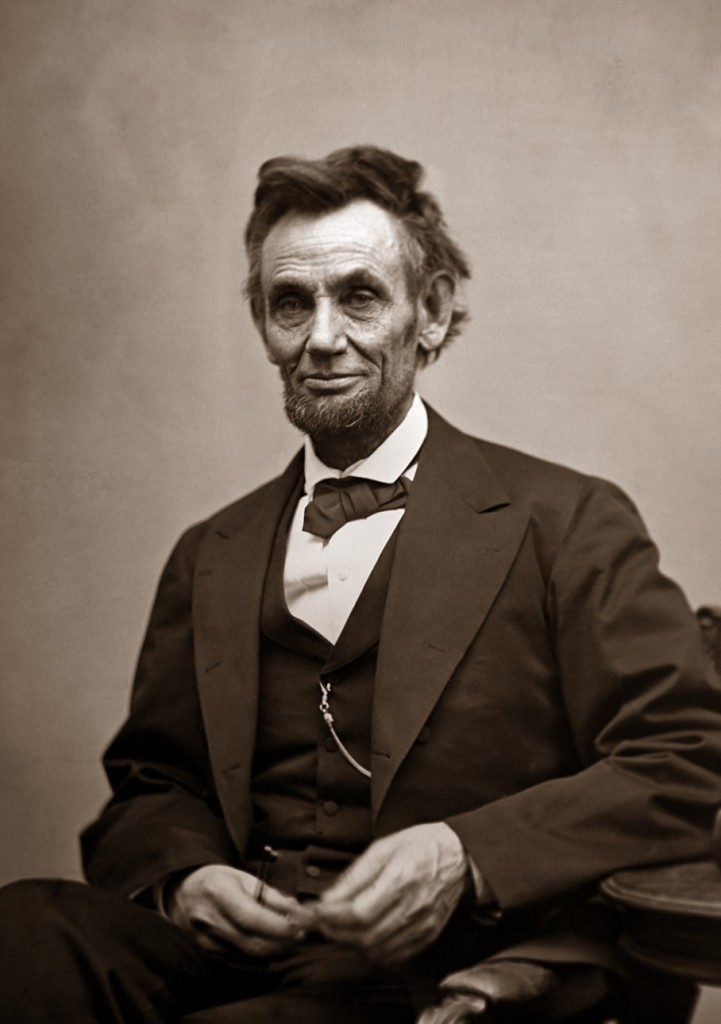

It has not always been so. The intense emotions that built over 30 years and exploded in the war that cost over 600,000 lives and immense destruction were for decades an acute sensation in the hearts of both north and south. The events at Appomattox that culminated in the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9th, 1865 were documented in the previous Ramparts, but the final act of the tragedy that forever secured the sacristy of the conflict was the murder of the national leader five days later on April 14, 1865. In a conflict that demanded the loss of so many, it was the almost Christ like death of Abraham Lincoln that seemed to stop the process of destruction forever in its tracks, as if a provision for washing the sins away for a wayward people had been pre-ordained. The stolen life of a single man seemed to bring a closure not possible through any other contemplated outcome.

On April 14th, 1865, the President of a United States that had fought an epic battle with itself for its very unity, was reported by many observers that day to be in an especially ebullient mood. He participated in a productive cabinet meeting in which he laid out his determination to steer a magnanimous course for the nation’s reconstruction, and for the first time in many nights planned a strictly social outing that evening to attend a popular play currently playing at the Ford’s theater in Washington ,Our American Cousin. He had invited his victorious general of the armies, U.S. Grant, to accompany the President and his wife, but due to a relative lack of comfort the two wives had for each other, Grant deferred. The President looking forward to the life affirming experience of laughter after so many years of crushing responsibility and tragedy, determined to go anyway.

It was Lincoln’s fate that the leading actor of the playhouse, John Wilkes Booth, saw himself as an actor on a far greater stage than that of the local theater, and had for months determined to play a defining role in history. The headmaster of a particularly bizarre gaggle of malcontents and miscreant Southern sympathizers, Booth self-identified as the avenger to reverse the fortunes of a conflict that the South had for months progressively pointed toward defeat. With the South’s defeat assured with its army’s collapse at Appomattox, Booth somehow convinced himself that with an epic sacrifice, the tide would be reversed. The cleansing act would be the decapitation of the Union leadership, with the violent deaths of the President, leading General, Vice President and Secretary of State to so shock the North that it would sue for peace and give the South the breathing room it needed. The cockamamie plan required the simultaneous actions of multiple conspirators, but Booth gave himself the honor of removing the hated victorious President .

It was a sign of the innocence of the times that Booth and his fellow conspirators came as close as they did to accomplishing the calamitous plan. As the President sat in the Presidential box at Ford’s to enjoy the play, Booth’s fellow conspirators fanned across Washington to remove the other stalwarts of government. The conspirator Lewis Powell showed the most malevolent commitment, entering the house of the Secretary of State William Seward, viciously attacking Seward’s son nearly killing him, then cascading up the stairs of the residence to enter the bedroom of the prostrate Seward, who had been severely injured in a recent carriage accident and was recovering. Slashing with a knife, Powell nearly killed the Secretary of State before being incapacitated by the Secretary’s other sons and household servants. The conspirator Atzerodt was positioned at the Willard Hotel, the residence of the Vice President of the United States, Andrew Johnson, but lost his nerve to attack and went off to get drunk, thus saving the Vice President for the honor of replacing the irreplaceable.

The penultimate act was left to Booth himself. The President resided at the theater in a box accompanied by an army major, Henry Rathbone, Rathbone’s fiancé, and the President’s wife. The President’s security detail was, stunningly given the emotions of the times, a single police officer, John Frederick Parker, who determined to be across the street at a tavern during the play’s intermission and never returned, leaving the President accessible to anyone who determined to enter the box. Booth, as a celebrity, had no problem entering the Presidential box, and waited for an acknowledged line in the play that never failed to bring laughter across the house. With the comedic line delivered, the President leaned back and with his last conscious act enjoyed a final moment of relaxed joy, as Booth positioned himself directly behind the president, placed a revolver against the President’s head – and fired.

A single bullet from close range entered President Lincoln’s brain from the left and lodged behind his right eye, and for all intent he joined the hundreds of thousands who passed in the war’s previous days and years, as the final sacrifice of a country’s death spasm. The laughing crowd did not immediately interpret the muffled shot as apart from the play as the terminally wounded President slumped forward, then back, but the experienced Major Rathbone recognized the sound and scent of gunpowder and sprung into the assassin. Booth struck him with a knife and managed to free himself from Rathbone’s grasp, then leapt from the box only to catch his boot on the patriotic bunting and awkwardly fell the twelve feet to the stage , breaking his ankle. The 1700 attendants to the nation’s first presidential assassination slowly grasped the reality, and turned their gaze to the box, then to Booth as he exclaimed an oath, eventually codified in legend as “sic semper tyrannis” – “thus always, to tyrants!”, though the actual words were heard differently be every shocked person close enough to hear them. Booth ran off the stage and into history as devil incarnate, destroying any chance the nation had at a measured and wise reconciliation.

The unconscious President was brought across the street to the Peterson House, where military surgeons quickly determined the wound to be fatal. So began the vigil of the President’s family, government leaders, and the nation, with President Lincoln drawing his last breath at 7:22 am on April 15th, 1865. As word spread of the events of the night and the President’s death, the stunned realization that the President who had somehow shepherded the country through four years of incalculable horror, had at the very moment of triumph and peace, been sacrificed at the altar of a sinful nation, progressively took hold. Lincoln, in life, who had been viewed variably by the many touched by the conflict, began to assume in such a senseless death, a sanctification that seemed almost inevitable. A man who had come from the simplest of roots, had grown to lead a people with an almost devine sense of the way forward when many around him felt lost. The careful and gracefully beautiful language, the context of the words, the steady and careful hand of leadership, the bottomless well of humanity inherent in this man came to represent the whole of the goodness of those who endeavored to leave their homes and safety and risk all for the concept of a just cause.

The funereal journey seized the national consciousness, as did the furious manhunt for the conspirators. The murderer Booth met his end 9 days later in a shootout at a Virginia barn; the other conspirators were hunted down and eventually met their fate at the end of a hangman’s noose. The vengeance though complete, seemed so unequal to the loss.

With the passing of the years, Lincoln’s stature has grown to where he is seen as the equal of the greatest of leaders in human history. As Secretary Stanton preciently stated upon witnessing the moment of the great man’s death, “Now he belongs to the Ages..” A man so much of his own time, Lincoln spoke of the potential of mankind as God’s vehicle for a better time, to be touched, as he so beautifully expressed, by the better angels of our nature. In our current day, where horrors once again abound, Lincoln’s profound humanity soars above his moment on earth, and truly belongs to our age every bit as all the others. In such ageless humanity, lies for us the slightest glimmer of hope.