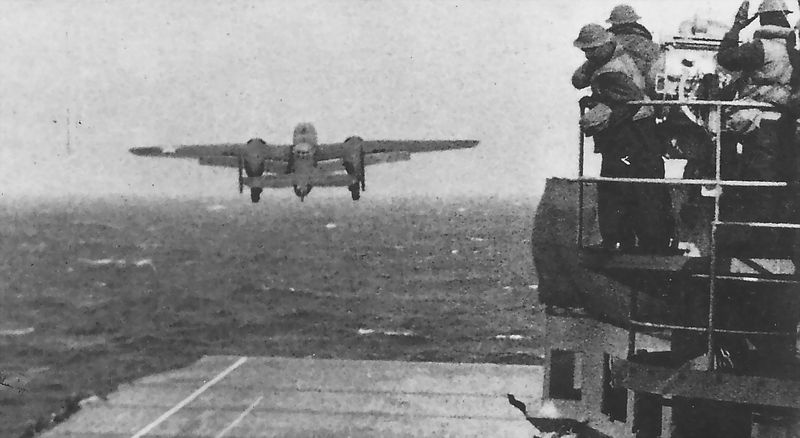

In the lead plane, the fuselage visibly shook as two massive engines strained against the restraints, driving rpms sufficient to create the escape velocity needed to lift the fuel and munition laden bomber across and safely off the short 500 feet of flight deck available to them on the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. In the co-pilot seat sat Richard Cole, a 27 year old Army Air Corps pilot picked by his squadron leader Lt. Colonel James Doolittle, who likely gave him a brief nod in the noisy cockpit as the time to accept history was upon them. No real time for nerves. 15 bombers and 75 crewmen behind them, waiting restlessly for them to clear. Waiting since December 7th, 1941, to show the Empire of Japan the United States was wrong country to pick a fight with.

After the catastrophic surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States and allied powers were reeling from a well supplied and well trained imperial Japanese force trained in the most modern equipment and imbedded with the most ancient martial ardor. Ruthless and efficient, the Japanese spiraled into the South China Sea imperiling the Philippines, with a tendril of American force clinging to Corregidor. The strategic thinkers in Tokyo strove to convince the Americans and British that their destiny in resistance was in ignominious defeat, and they convinced themselves and their population that the battle would be fought on foreign lands away from the sacred homeland.

The Americans had their own psychology to worry about. The greatest economic force in the world was well over a year away from adequate force projections against such a difficult foe, and it was not clear how long the American public would be able to tolerate defeat after defeat. The goal after Pearl Harbor by American strategists was to eliminate the aura of Japanese invulnerability, and crack the fantasy of superior racial will and capacity for sacrifice for the Emperor. The Japanese had shocked the Americans with a complex and massive multi carrier strike across 3000 miles of ocean destroying a large part of the American navy at Pearl Harbor. How could the Americans now with no functioning battleships, and 4 overstretched carriers possibly achieve a similar psychological blow? The answer was divined By Lt. Colonel James Doolittle who almost immediately after Pearl Harbor envisioned a means of carrier projection that would strike the Japanese homeland itself and achieve an equally stunning psychological impact. The crazy idea was not to risk the few carriers the Americans had in a suicidal mission involving fighters and dive bombers with short flight capability that would require the carriers to enter Japanese waters and almost certain overwhelming defenses. No, the crazy idea was to do something everyone thought essentially impossible, to use the carriers from longer distances and launch heavy bombers that would strike the mainland of Japan and have sufficient fuel capacity to continue to China, and land…. Crazy.

Doolittle, a test pilot and engineer, first proved on land he could take off on an extremely short runway on land then proved it on a carrier. The mission would require bombers to fly as much as 2400 nautical miles to complete the mission, but nothing mattered if the fully armed planes could not even get off a flight deck. With modifications, Doolittle had found his plane, the Mitchell B 25B midrange bomber, and in the three months since Pearl Harbor sufficiently modified it to achieve the concept of the mission. President Roosevelt, willing to try anything to gain a foothold with the American public in a sea of bad news, approved the mission, and the meticulous process of picking crews that were willing to try something never done before on a one way mission with no direct home of return was left to Doolittle. 80 men eventually formed Doolittle’s 17th bomber squadron, and on the second of April left the Alameda Naval Station loaded on the USS Hornet for the long trek across the Pacific.

The plan was to get sufficiently close to Japan to allow the fuel necessary to safely land in China, but on the morning of the 18th of April, the task force was spotted by a Japanese scout ship, and Doolittle and the Hornet captain, Mark Kitscher, determined to launch the bombers given the loss of the element of surprise, despite being a full 10 hours earlier and 170 nautical miles further out than planned. The Hornet was turned into the wind. Doolittle piloting the lead plane, and the 15 bombers behind Doolittle and Cole then accomplished the impossible in 40 minutes, all successfully launching a munitions laden bomber from a carrier flight deck, though none of them had ever done it before, or would do it again. Flying low to evade detection, over six hours of nerve wrenched flying were required to reach the target, Tokyo, but the insane nature of the attempt contributed to the Japanese complete surprise, and the bombers rose to 1500 feet and managed to strike the heart of the Japanese empire, Tokyo with over 2000 pounds of incendiary bombs each. The physical damage was relatively minimal, but the psychological damage to the Japanese was immense. It was clear that America had determined that the pain of war would be felt on the Japanese mainland from the war’s very start, and an ominous hint of what was to come, entered the Japanese psyche.

The brief glory of the successful raid rapidly turned to desperation for the flight crews as their realized the increased distance required to fly by the early launch had stolen their fuel reserves. Some managed to reach the Chinese mainland into the hands of allied forces, but others had to ditch into the sea, and one crew was force to abandon their plane on Russian soil. Of the original 80, 69 escaped capture or drowning, 3 were killed in action, and 3 others were eventually executed by vengeful Japanese forces. Doolittle and Cole were among the 69 to return, and were among the pilots would fight again, and contribute to the eventual massive air destruction of the Axis powers. Doolittle would receive the Medal of Honor and military immortality, and Cole the Distinguished Flying Cross and the pride of a job well done.

Which brings us to Richard Cole, the co-pilot of Doolittle’s lead plane on the Tokyo raid, who stood at 101 years of age on April 18th 2017, the last survivor of the those heroic airmen who 75 years ago achieved the first blow against Japan in a mission so impossible no ever tried it again. Every year after the war to celebrate their accomplishment, the men of the 17th bomber squadron would get together on the anniversary and toast their fallen comrades. A stand filled with upright goblets, upon which each goblet was etched with the name of a surviving raider, was placed in the room, and as time took crew members, each was toasted with cognac, and the goblets of the fallen were successively overturned. With each decade the numbers of upright goblets grew fewer and fewer, and the group’s mortality was etched for all time when Doolittle’s goblet was turned over in a toast to their fallen leader in 1993. By 2016, there were just two left, Cole and 94 year old David Thatcher, and on June 22, 2016, Richard Cole was the last man standing. On April 18th, 2017, the final goblet remains upright, and it has become Richard Cole’s destiny, to be the Last Raider standing.

The men and women of the magnificent generation that braved all to save the world from a dark, soulless future are rapidly leaving us forever. They are now only faint memories in faded photographs, flickering newsreels, and history books. But everything they were, they always will be, as they faced true madness and through heroic sacrifice and personal will, gave us all one more chance at a better world. To all the World War II veterans, from Richard Cole, to my own father, God Bless you and thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Oh, how you soared like eagles.

Oh, how you soared.