In 1776, the highest form of capital crime in the United Kingdom or the vast expanse of colonized lands under the sovereignty of King George III was the crime of high treason, disloyalty to the Crown. The concept of high treason represented the ultimate attempt to distort or erode the authority of the sovereign and for hundreds of years represented the ultimate moral stain on a subject of that sovereign. As such, the punishment for such a heinous crime was defined under law as equally heinous — drawing, hanging, and quartering. The traitor would be drawn to his place of execution, hung in a fashion insufficient to kill him outright, then eviscerated and quartered while still alive so that he could experience the full extent of the torture before being beheaded. The sentence of forfeiture, the assumption of all lands and possessions of the traitor and all relations followed the direct sentence, assuring the position of the traitor was forever wiped from any societal stature forever more. Among the various crimes reflective of such high treason was a subject undertaking premeditated war against the sovereign.

The 56 men who formed the Second Continental Congress could not help to have a visceral foreboding sense of such a personal outcome potentiated by the proposed actions they debated through the spring and hot summer of 1776. The Second Congress had been called as a consequence of the outbreak of war against the sovereign’s army in April, 1775 outside of Boston, culminating in a surprise victory for the colonials and an ignominious defeat for the king’s forces in March, 1776, resulting in the withdrawal of British royal forces from Massachusetts. If the colonial representatives of the Congress had hoped the King had any intentions of pulling back from brink of total insurrection, he quashed them rapidly with the passage of the Prohibitory Acts, that blockaded all American ports and declared all American vessels enemy vessels, assuring a continent wide crushing economic burden. it was fully apparent to all thirteen colonies that their persistence in meeting as a collective assured them a collective consequential verdict in the King’s eyes. Bandits. Rascals. Traitors.

The Age of Enlightenment began as a scientific revolution, but exploded into a golden age of philosophic thought not seen since the ancient Greeks. The power of reason surged through a 100 year renaissance of the ideas of Descartes, Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Spinoza, Hume, Locke, Kant and Smith that dominated the advanced education of any gentleman of the 18th century and infected an entire generation learned men not only in England, Scotland, and France, but the entire continent and the New World. The concepts of innate individual rights, rational society, and the concept of common men in charge of their own reason and destiny struck directly at the heart of the concept of divine rights of kings. The concept that a King through edict could impel subjects to defer these rights without any representation of their opinions to influence seemed antithetical to the generation currently standing as leaders of the American colonies. Americans saw themselves as having lived an almost 170 year experiment in independent incentive required to survive the harsh consequences of having to colonize and civilize a harsh and wild continent, and though loyal to the concept of being essentially British, assumed that the process that was borne at the Magna Carta, Glorious Revolution, and ascension of Parliamentary representation was their history as well. Great Britain had many colonial dominions, however, and the King could not cotton one set of colonies securing rights and privileges he would then have to inevitably accede to in all others.

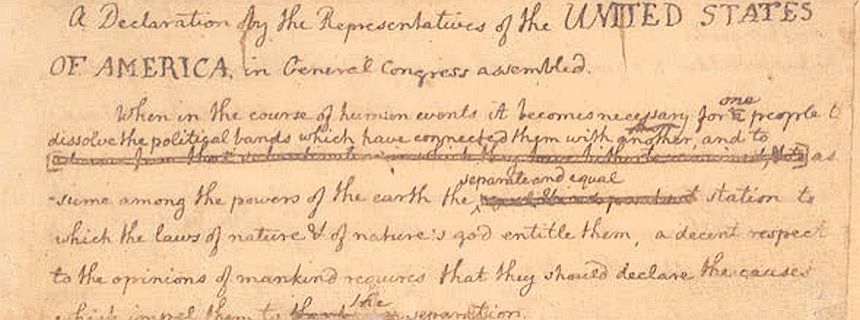

In the spring of 1776, there was certainly no unanimity of thought as to the direction to take to address the developing crisis. Each of the thirteen colonial legislatures felt themselves unique in governance and provided contrary instructions to their representatives of the Congress, but the tide of opinion was swelling toward a more profound separation than most wanted to admit. The radical north, having felt the violence of insurrection directly, led by John Adams of Massachusetts, proposed a Preamble of a potential resolution for separation from the mother country. At the same time the Virginia convention, the legislature of the most prosperous and influential colony, on May 15th, 1776, proposed that the Congress debate a resolution to declare the colonies free and independent states, absolved from all allegiance to great Britain. In light of this edict, Richard Lee, the Virginia representative, proposed to the Continental Congress a debate over a three part resolve to declare independence, form foreign alliances, and prepare for a trans-colonial confederation of states. The motion was seconded by John Adams, and cold hard reality of the commission of high treasonous acts was now an unavoidable possibility for every delegate. The profound maneuver was truly revolutionary and multiple delegations did not feel they had sufficient power to declare for their associated colonies without further instruction. The resolution was therefore tabled, and a three week recess was called, while delegates could return home to their legislatures for further instruction. The Congress appointed a committee of five, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman to develop a definitive declarative statement. The language was definitively Jefferson, but contributions of Adams and Franklin brought clarity to important segments. The above photo shows the influence of corrections applied to Jefferson’s hand written document in real time by both the committee and subsequently the congressional delegates themselves. The eventual Declaration of the Continental Congress as envisioned by the authors became a document of the very principles of the Enlightenment highlighted by the single statement that defined all subsequent actions and has resonated through all humanity for the next 242 years:

We hold these truths to be self evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and Pursuit of Happiness.

No statement had ever firmed the conviction of undertaking the obvious risks of separation from a ruling power based on the stance of inherent rights borne of men. The argument that such rights were endowed by the Creator, and therefore preceded any worldly declaration of governance was so revolutionary that the very statement if somehow able to be realized, would forever remove the divine rule concept that had dominated all society since the dawn of the tribe. To sign such a declaration was to state the sovereign never held any such rights of dominion in the first place. There could no rationalization of the statement as anything other than the highest treason in the case of an eventual defeat for any of the delegates who would endorse, and they knew it.

On July 1st, the Congress reassembled and the Declaration was debated in earnest, with significant adjustments and substantial shortening agreed upon to strengthen the document and improve its impact. Considerable angst was felt by many, and the capacity for an unanimous declaration was in doubt. Benjamin Franklin rallied the delegates with the clarifying focus of the importance of unanimity:

‘We must hang together, or surely we will hang separately.’

On the evening of July 1st, the Congress after a full day of debate took up the edited Declaration of Independence and advanced to the roll call of the individual delegations. No doubt each faced the enormous weight of history of such a declaration against the King of the most powerful nation on earth, both personally and as the leading edge representation of their fellow Americans. The initial roll call had dissent from South Carolina and Pennsylvania, and abstention from New York. The exhausted delegates determined to table the resolution until the following morning. The overwhelming weight of holding back history smothered the Carolina and Pennsylvania delegations through the night. On the subsequent morning July 2nd, 1776, the roll call was again taken and South Carolina reversed its vote, and the lonely dissent fell to Pennsylvania. Though personally against the declaration, John Dickerson and Robert Morris bravely abstained so the declaration could be voted upon by the residual five members of the delegation. A 3 to 2 vote in favor resulted and the last holdout Pennsylvania fell into the approval column. With no residual dissent the Declaration passed, and the convention declared the colonies Free and Independent States.

One can only imagine the sense of stunned silence that must have permeated the hall as the delegates fully absorbed what they had just done. Though the public proclamation followed on the 4th of July, the future of the world was sealed on July 2nd, 1776 as the foundation of a concept of a governance underwritten by individual liberty and property, self governed, would have its birth forever recognized from this seminal vote.

Two hundred and forty-two years later, living testimonially in the greatest semblance of liberty and individual rights ever assembled, we celebrate the gentlemen on that oppressively hot morning in Philadelphia who faced an impossible task fearlessly because of the overwhelming surety of their cause. In an age where the liberties so dangerously promoted and so painfully sacrificed for are frivolously given up for a transient sense of security, the moment needs to be re-lived.

Life. Liberty. The Pursuit of Happiness. Let the bells ring out and the drums peal! Happy Independence Day.

Thank you once again for making history come alive. Currently, our President is being accused by some of treason. It could be argued that the acts of the Department of Justice, FBI, and Clinton Campaign come much closer to the definition. Yes, we have given up freedom for security and sovereignty for the saccharine and superficial ideal of ‘open borders’. Emotion blares over reasoned thought, and censorship is preferred to an open market of debated ideas.