A quant relic of a long ago age that in preceding decades was quite commonplace among small towns throughout the eastern half of the American continent, is a now rarely witnessed event – a civil war battle re-enactment. Local and regional commonfolk would take the opportunity to meet in bivouac, dress in period clothing, utilize uniforms and arms consistent with the Civil War era, and re-enact major battles of the war on a farmer’s field or semi-forested prairie to link themselves, in some fashion, to ancestors long gone who had participated in the very real thing. Crowds would gather to see the camps, watch the maneuvers, smell the gunpowder, and immerse themselves in what it must have been like to have left home and risked all in a battle to save a nation, or defend a home state. The untold message of such events was the quiet dignity reflected of having achieved a modern modicum of tolerance for each others views, that had at one time had created a state of passion so intolerable to live within, that it could not be salved without a fight to the death . The war itself, as the culmination of a decades long ever more intense disagreement of the very nature of the nation’s founding, was foundational class work material for all educational levels to attempt to deal with the logic and decisions that led to a tragic conflagration and almost a hundred years of subsequent strife, to both live up to and eventually make the nation worthy of the terrible sacrifice.

The re-enactments helped bring palpability to the history that ran through the veins of both participants and onlookers. History of such intensity that emotions at the sight of a battleground, a flag, or gravesite are still capable of tears 160 years later. It is a history current cultural warriors try to simplistically frame on racial terms and paint the country’s spasm a outgrowth of original sin, the ugly stain they glean from the nation’s very founding. The re-enactments have been demeaned, the statues removed, the anniversaries ignored, story tellers reviled. It is easier to redefine the issues and causes in a more indoctrinatal way if the palpable reminders are physically eliminated.

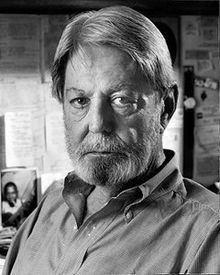

There are bulwarks against the modern revisionism. Ken Burns created in 1990 a special form of palpable history with his miniseries cinematic essay on the American Civil War. It introduced a humanity to the events and combatants that prevented easy labelling, and brought to celebrity a heretofore obscure southern novelist and historian to immense national prominence – Shelby Foote. Foote had spent thirty years of his life producing a history of the war that emulated an ancient Greek tome. Told in the vernacular and view of the times, heroes and villains, dangerous and enormous trials of courage, surprising warrior complexity and moments of sheer terror and boredom, the three volume trilogy spoke to the essential essence of the people of the conflict, and the conflict that made or broke them by the thousands. Foote translated to Burn’s cinema a tragic timbre to the events and engrossed millions of viewers who had only peripherally connected with the conflict. Foote brought his unique perspective of the foot soldier and particularly the southern infantryman, of whom it is simplistically assumed were motivated by race and the slavery issue. As Foote reminded all, the great majority of southern soldiers owned no slaves and had no direct investment in this part of the conflict. As Foote explained, when the southern soldier was asked his motivation for fighting so fiercely, he often retorted, ” its because you’re down here.” Place meant more then anything when armies threatened homes a thousand miles distant, in a time when most had never been thirty miles away from their own home. Foote’s soft drawl, deep insight, and novelist framing made for riveting history. As Homer had his Iliad, Foote’s treatise helped bring a tragic beauty to a dark and violent story.

So as you might imagine, thirty years later, as statues of heroes come down to serve the modern narrative, the cancel culture has turned its heat on Shelby Foote. Foote died in 2005 at age 89, and thankfully is not around to see the frivolous assault on 19th century history and southern symbols. His Wikipedia page however is laced with efforts to degrade his southern view into racist doggerel and try to link him to prejudice and hate. It is anathema to imagine something trying to explain the world view of the average 19th century American without correcting with 21st century caveats. The historical ignorance of such approaches avoids the very real, complex arguments that made a peaceful evolution to the ideals of equality so difficult – concepts of destiny, tribalism, states rights versus founding philosophies, societal hierarchies throughout history. Despite all, the country found the courage to test its original idea of all men are created equal in an existential conflict, that destroyed huge swaths of the country and took nearly a million lives to answer in the affirmative. People didn’t hold the views they held regarding society because they were stupid, they held them because they felt their own world view deserved existence in a revolutionary society. Foote gathered from his own ancestors, the stories of his youth, and his own sense of the sweep of history to bring alive the distant time in a manner few others have ever done in explaining the American experiment .

If you are willing to listen to distant voices to better understand own own times, read Shelby Foote’s magnificent history, watch the Burns cinematic miniseries, immerse yourself in the Lincoln Douglas debates, and take time to read both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglas. A years investment of time will bring you ever closer to a nuanced and rational grasp of your own time, and avoid the silly nonsense of our current “experts” on what plagues society. We should never be afraid of what inspired us in an earlier time, and Shelby Foote gave us one of the great reflections of our all too human journey.

Thanks for sharing your wisdom and knowledge—and the great recommendations at the end! Our current times need this ‘common sense’.