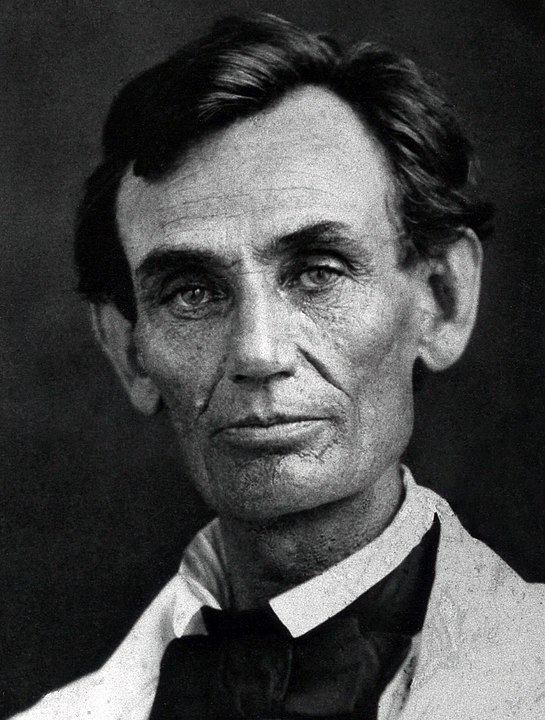

We are in a time of deconstructive destruction. Marxian critical theory, the specific economic radical thought that bluntly separates the world into oppressors and the oppressed, and formulates the process of unmasking and liberation from the ideology that justifies keeping the later oppressed, has morphed, for a myriad of today’s political agendas, into a tidy weapon to destroy history’s icons and reframe them into useful villains. Among the most olympian of icons pinpointed for destruction is Abraham Lincoln, who epitomizes the kind of target that makes all further deconstruction possible. To destroy the exalted image of Lincoln as the great emancipator, is to make all the underpinnings of America’s foundation and its very reason for existence suspect. Lincoln, perhaps more than any other leader, lived an uncluttered, sophisticated understanding of the deeper tenets of the unique American ideal, and infused them into every thought and action he took through some of the most difficult and calamitous trials any historical leader has faced. Lincoln’s deeper understanding and the eloquence with which he espoused it, is the colossal shield that resists the innumerable petty attacks that seek to make him just another of our destructed heroes. Abraham Lincoln was born to the most humble of circumstances in La Rue County, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809, and as we are now 213 years from that seminal moment, Ramparts looks to see if Lincoln the man still holds up to our memories as the avatar of the American miracle.

In today’s world of elitest prejudice that assumes only an elite ivy league institution could possibly prepare a person for greatness as a leader, the circumstances of Lincoln’s unfathomably humble creation and upbringing make the eventual perceived brilliance of the man all the more confounding. David Reynold’s magisterial biography, Abe : Abraham Lincoln in his Times, presents a multi-layered pallet as to the cultural mores and personal interactions that made a Lincoln possible in such a forbidding and challenging landscape. Lincoln was born in 1809 in Hodgenville, Kentucky in the wildest and most threatening of worlds abounding in dangerous, wild animals and hostile natives. Lincoln’s own grandfather had been killed in an Indian attack witnessed by Lincoln’s father, and survival was a personal, daily challenge. Organized education was essentially unheard of , and the young Lincoln children were expected by their father to do utmost to physically support the family in the dramatically hard wilderness existence. The development of an intellectual core had no immediate worth, and no obvious core. The first hint of a character construction that separates the Lincoln experience was the contrarian nature of the Lincoln family’s Baptist faith, built upon abstinence from “alcohol, dancing, and slavery” in Kentucky, a slave holding state where two of the three “sins” were considered part of the cultural connectiveness in the wilderness, and the third, a not unreasonable tool to augment survival in a harsh environment. The Lincolns saw it differently, and to whatever future influences modern society impelled upon Abraham Lincoln, alcohol and slavery remained antithetical to his being.

The Lincoln family lived the classic trial of the American pioneer. Having failed in finding prosperity in Kentucky, the Lincolns, rather than contracting back toward their legacy family in Virginia, moved ever more west, first to Indiana to even more wild circumstances, and then Illinois, in search of the vague concept of personal opportunity. It was to elude Lincoln’s father Thomas, but through the incredible circumstances of unpredictable fate, land upon his son Abraham in an almost providential manner.

For no obvious reason, young Abraham Lincoln became infected with the “bug” of the intellectual search for meaning. He devastatingly lost his birth mother Nancy Hanks to the wilderness plague of “milk sickness”, poisoning from cow milk tainted by tremetol, a byproduct from cows eating snakeroot and goldenrod. His father acknowledging the critical matriarchal central role to survival in the wilderness, married the widowed Sarah Johnston, who took on the raising of Abraham and his sister Sarah as well as her own three children in a new expanded household. Unlike Thomas Lincoln, who saw no advantage to education over physical labor, Sarah encouraged Abraham’s untapped potential in reading and writing, previously interpreted by his father as an indication of Abe’s “lazy” tendencies with such pastimes. Despite accumulating a total of only twelve months of spotty formal education in his fifteen years of youthful development toward manhood, Lincoln proved a voracious reader of the available literature, the King James Bible, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Aesop’s Fables, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Shakespeare and Poor Richard’s Almanac and autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. It formulated in him for the rest of his life the value of a story linking to a deeper truth, and became a profound tool in his self taught but ultimately sophisticated powers of communication and persuasion.

The years of a developing abhorrence of isolation and wilderness tied to his reading of the larger world led Lincoln to seek a public life to define adulthood. He left his family initially to seek a life of commerce, transporting goods down the Mississippi and eventually working in a general store. It became clear to everyone who knew him that Lincoln had an unusual knack for developing strong communal bonds and lifelong relationships. His physical strengths and gentle demeanor allowed him to both survive challenges in the rough and tumble society of the midwest, as well as project a willing nature for self improvement and leadership. He was selected by his peers as captain of militia in the Black Hawk War of 1832, and although Lincoln was famously quoted as saying the only blood his platoon drew was from “a few Mosquitos”, he gained the kind of respect and deference that made him a candidate for the state legislature and eventually an successful assemblyman with the Whig party, and eventually serving in the U.S. House of Representatives as an Illinois congressman.

The famous “bug” of introspection and self improvement became ever more intense as he left congress after one term to “become” a full time lawyer. Self educated but enormously disciplined, Lincoln passed the Illinois bar in 1836. A voracious observer of his law partners propelled Lincoln to absorb their best traits and expand his reading to the extent that by 1852 was considered a formidable lawyer across the state, often appearing before the Illinois Supreme Court. Lincoln’s combination of principled approach and unrivaled honesty married to a folksy, yet sophisticated style of rhetoric became part of a growing prairie legend. The unexpected thrust toward national prominence came from Lincoln’s unswerving opinion regarding the national stain of slavery on the nation’s continuing development and destiny. His interpretation of the founders’ vision and the documents framing that vision, accompanied by his own observations and preternatural aversion from his upbringing led him to begin speaking out on a national stage that both risked his bounding law practice success and propelled him into the hottest of hot national flashpoints. The igniting fluid was the passing of the Kansas – Nebraska Act which opened the real possibility of the spread of slavery into new territories of the expanding United States beyond the restrictions of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 which had for thirty years worked to restrict slavery to the so called “cotton” states where cheap mass labor had been considered essential to their economies. Lincoln, as did many Northerners, felt the original intention of the founders was for the eventual extension of slavery to arive at a culmination of the promise of the nation’s founding, that “all men were created equal”, and that slavery was a vestige of imperial legacy that were antithetical to that premise. Lincoln believed in the concept of “evil”, and felt slavery was an “evil” to which an economic justification could not surmount its innate injustice. Lincoln was further empowered by the demise of the Whig Party, from which a new federal economic vision was married to an old abhorrence of the concept of slavery in the new “Republican” party. Lines were being drawn, and Lincoln “out of nowhere” as defined by eastern elites began to progressively become the intellectual voice for anti-slavery forces.

The Dred Scott decision of 1857 was the defining event in the ascension of Lincoln from country lawyer to national standard bearer. The U.S. Supreme Court accepted the case of Dred Scott, a slave whose master had taken him from a slave state to a free state as determined by the Missouri Compromise. Scott petitioned the court that the transfer to the laws of a free state had made him a free man, an he was not under any obligation to return with his owner as a his slave to his original slave state. The court ruled that blacks were not citizens and as such drew no protections from the U.S. Constitution. The implied concept that humans determined as “property” functioned under laws of property were abhorrent Lincoln and out of the prairie-hewned folksy style grew a much more august voice firm as iron on a deep understating of the principles of free will and liberty Lincoln was convinced was forever engaged by the nation’s founding.

The fully evolved Lincoln that would define his legacy needed a national platform, and sought it in taking on the popular designer of the Kansas Nebraska Act, Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois. Nominated by the Republicans enthusiastically in their state convention of June 16th, 1858, Lincoln brought to bear incendiary language to the national discourse that fundamentally defined the slavery question as an existential risk to the future country:

“A house divided against itself, cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become lawful in all the States, old as well as new — North as well as South.“

Douglas who saw himself as a conciliator that managed to keep the country out of conflict, believed Lincoln was the match that would incite conflict, and agreed to make their race a national debate for the slavery question. He engaged Lincoln in a series of debates that held Lincoln off from the Senate seat but was the very platform that projected Lincoln into national prominence that allowed him to defeat Douglas for the U.S. Presidency just two years later.

The debates are a one of a kind recorded forum of what political debate is idealized as, but almost never realized. Multiple sources are available of the entire series of debates held between two rhetorical giants that would define the opposing views for all time, and both men and their cultural prejudices, were of their time. There can be however no clearer framing of the argument, than Lincoln’s spectacular July 10th retort to Douglas’s July 9th Chicago speech he had been invited to attend.

“Those arguments that are made, that the inferior race are to be treated with as much allowance as they are capable of enjoying; that as much is to be done for them as their condition will allow. What are these arguments? They are the arguments that kings have made for enslaving the people in all ages of the world. You will find that all the arguments in favor of king-craft were of this class; they always bestrode the necks of the people, not that they wanted to do it, but because the people were better off for being ridden. That is their argument, and this argument of the Judge is the same old serpent that says you work and I eat, you toil and I will enjoy the fruits of it. Turn in whatever way you will—whether it come from the mouth of a King, an excuse for enslaving the people of his country, or from the mouth of men of one race as a reason for enslaving the men of another race, it is all the same old serpent, and I hold if that course of argumentation that is made for the purpose of convincing the public mind that we should not care about this, should be granted, it does not stop with the negro. I should like to know if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle and making exceptions to it where will it stop. If one man says it does not mean a negro, why not another say it does not mean some other man? If that declaration is not the truth, let us get the Statute book, in which we find it and tear it out! Who is so bold as to do it! If it is not true let us tear it out! [cries of “no, no,”] let us stick to it then, [cheers] let us stand firmly by it then.”

And with rhetoric of the need for the extirpation of evil, Lincoln brought to bear the whirlwind of the War of the States that was ignited by secession and was framed by even Lincoln as a war to subdue the rebellion and reunited the country. Millions of words have been written that place Lincoln through his actions in various roles from hero to villain in the calamity. The core fundamental of his actions and the eventual cause of his martyrdom is an undeniable truth – he saw slavery as a great evil -an evil vestige of an earlier time that had somehow survived and attempted to expand in a land premised on the principle of “all men are created equal.” This inequity, this injustice he could not stand by and let be, and in the triumph of good over evil, 700,000 souls of varying implicitness in the sin, including himself would require sacrifice.

Abraham Lincoln was a man of his time in his personal prejudices, but his incredible personal growth and deeply held personal convictions as to right and wrong brought clarity to such arguments for all time. It is the intellectual laziness of a dullard, the vacuousness of a self righteous fool that does not recognize the timeless gift that was Lincoln, and how much he has to teach us about each other, and the importance of holding firm to that which was born of the better angels of our nature. Happy birthday to the Great Emancipator. At 213 years since God created this particular miracle, he holds up quite well indeed.

Well said Bruce!!

Oh to see another of his convictions succeed and rise to the top! Thank you Bruce!