On January 20th, 2025, a time-tested process of peaceably turning over the reins of power in the world’s oldest functioning democracy, from one Chief Executive to another, will take place. Not that there isn’t some drama proceeding this event, as has often been the case from the founding of the nation under the current Constitution. One only has to go back to the proceeding inauguration of President Joseph Biden on January 21st, 2021 to see how dramatic it can be.

The Constitution was structured to avoid a direct democracy securing the executive. Each state is empowered to provide a slate of electors proportional to its elected legislative contribution, who based upon and subsequent to the November election, meet in December of the election year as an Electoral College to submit the vote for a President and Vice President executive. On January 6th of the following year, the newly elected Congress is to certify the Electoral College vote, officially electing the two executive officers. Two weeks later, the Chief Executive, the President is sworn in under the auspices of an inaugural ceremony.

Well, that’s at least how it’s supposed to work.

The assumption is the Electors are to accurately reflect the electoral outcome of the state they represent. The 2020 election outcome was however fraught with concerns regarding its integrity, and was challenged by one of the candidates to the extent that there was talk about some states presenting alternate elector slates. The tension exploded on January 6th, with a riot breaking out outside the Capitol building as the legislature inside was undertaking the certification vote, intense enough to be politically described by the winning party as an “insurrection”. An effort to impeach President Trump for a second time on January 13th, 2021, based upon his supposed incitement of the effort to delay the certification of the electoral vote was approved by the House of Representatives. Incoming President Biden aggressively directed his Department of Justice to pursue harsh retribution for the “insurrectionists”, and the second Trump impeachment concluded with a Senate acquittal, for the first time an impeachment adjudicated three weeks after the impeached executive was no longer President.

If everything this time goes smoothly, the aforementioned twice impeached and imperiled 45th President, Donald Trump, will be sworn in as the 47th President of the United States, at the January 20th, 2025 Presidential Inauguration ceremony.

No one ever said this democracy thing wasn’t interesting.

The Inauguration ceremony that is going to culminate in the improbable return to the Presidency of Donald John Trump has much to contribute to the colorful fabric of the American story. For those assuming Donald Trump is a one-off to special circumstances or controversy framing the process, a look back at some of the nation’s inaugurations tells a different tale…

First Inauguration of the 1st President George Washington – April 30th, 1789 : The very first Inauguration holds many unique qualities. First of all – it was the first. With the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation becoming more and more apparent, a Constitutional Convention met in 1787 to develop a federal Constitution, eventually, establishing with some tumult, a bicameral legislature, Chief Executive, and Judicial branch. Finally approved by a majority of states in September of 1788, the mechanisms for the first federal governing bodies were set on a timetable for the official start for the new government on March 4th, 1789. The second Article, establishing the Electoral College mechanism for electing a President and Vice President, was put into play for the first time, and, predictably, presented issues which would soon require subsequent amendment. The Electoral College was designed to forward the highest and second highest electoral vote getters as President and Vice President respectively. No political parties were then in existence, but divisions ignited by the process forming the constitution already were apparent. Thankfully the highest vote getter was the universally admired Virginian and Continental General George Washington, who received unanimous support from all state electors. The second highest vote recipient, in the runner up position, was assigned Vice President. Of the 12 electoral candidates receiving a vote for President, John Adams accumulated the second highest total of 34 electors, defeating John Jay, Robert Harrison, John Rutledge, John Hancock, George Clinton, Samuel Huntington, John Milton, James Armstrong, Benjamin Lincoln, and Edward Telfair.

All elected officials were intended to be sworn in on March 4th, 1789, but it was a very different country then in regards to travel and distance. Only 8 elected Senators and 13 congressmen were present, insufficient for a quorum to certify the presidential results. Therefore, the inauguration of the new president was delayed until official certification on April 14th. George Washington was formally sworn in on April 30th, 1789, at the Federal Hall in City of New York, the nation’s first federal capital. He started a tradition of presenting an Inaugural address by the President to the nation. He reiterated his personal sense of obligation of service to the nation, and hope that he would be worthy of the task. He spoke to the providential “Invisible Hand” that had guided the nation to its unique position of a free and independent people. He lay forward his intention to promote only selfless and highly moral people to the executive that would preserve “the sacred fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government“. His first cabinet of Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Henry Knox, and Edmund Randolph certainly lived up to his standards.

His inauguration was met with universal celebration, and he remains the only President to have received a unanimous electoral vote for both of his two elections.

First Inauguration of the 7th President Andrew Jackson – March 4th, 1829: The election of Andrew Jackson to the Presidency in 1828 was transcendent. Jackson was the first president to have a massive populist electoral wave driven by the newly created Democrat Party carry him to the executive. The result flew in the face of the previous tradition of elevating a national “elite” positioned to assume the office. The Inauguration Day was emblematic with incredible crowds driving the inauguration proceedings into chaos. The crowd was estimated at an incredible 20,000+ – every one of them convinced they were Jackson’s personal invite. The swearing in ceremony was for the first time held on the East Portico of the capitol to allow for the larger crowds, but they pressed so tightly, that Jackson escaped out through the West side of the capitol riding his white steed to the White House. The celebration grew more intense at the White House Inaugural Ball as Jackson determined to invite all his supporters, with the throngs entering through doors and windows, accused of unruly drunkenness, smashing plates and furniture (alleged, but denied by Jackson supporters). Jackson eventually had to escape through a side entrance to prevent being consumed by the enthusiasm.

Jackson’s inaugural address spoke to several key considerations he claimed he would adjudicate with prudence and respect. He spoke to his willingness to accept the limitations of the executive as it pertained to state’s rights, and a desire to observe toward native Indian tribes “a just and liberal policy, and give that humane and considerable attention to their rights and their wants with is consistent with the habits of our government and the feelings of our people”. Jackson would belie his words in his subsequent aggressive actions toward the supporters of nullification, resulting in clashes with his Vice President John Calhoun of South Carolina and threats to “hang any insurrectionists” who defied federally legislated determinations. His abysmal policy toward indigenous tribes including the Indian Removal Act and the forced translocation of the Cherokee tribes from their ancestral lands, resulted in violent retribution against Creek and Seminole tribes who refused to move from their ancestral lands, culminating with the ignominious “Trail of Tears” saga.

Inauguration of 9th President William Henry Harrison – March 4th, 1841: Did an inauguration speech kill a President? William Henry Harrison, long-time governor of the Northwest Territories, famous Indian fighter, and as the candidate of the first nationally based successful opposition national party to the Democrats, the Whigs, won the 1840 election with a national narrative not particularly in keeping with his aristocrat Virginian background. Harrison was posited as the “rough hewn” Indian fighter, having defeated a confederation of tribes led by Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe, fought at the confluence of the Wabash River and Tippecanoe Creek in the Indiana Territory in 1811. The Whig campaign was driven by the successful weaving of the narrative of Harrison as a man of the common people, by attaching the symbols of “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” firmly to Harrison. For the federalist inspired Whigs, a Harrison narrative in keeping with the mythic status of Andrew Jackson was necessary to overcome the voters’ suspicions of elites, so carefully cultivated by Jackson through his political career. William Henry Harrison was however far afield from the curriculum vitae that defined Jackson. Harrison was born into a family of the Virginia landowner Tidewater Aristocracy. His father was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and governor of Virginia. Harrison was highly educated and upon his successful election to the highest office in the land, wanted to use his inauguration as an opportunity to secure his association with the founder Presidents, and away from the his mythic hard scrabble persona.

Harrison proceeded to write an inaugural speech that would announce his intellectual bonafides. He personally prepared a multi-thousand word speech intended to project classical intellectual chops and a level of endurance that would alleviate public concern regarding his advanced age of 68 , the oldest President to be elected prior to Reagan. The Massachusetts intellect Senator Daniel Webster, who would become Harrison’s Secretary of State, was requested to edit Harrison’s self written speech, projected to run two and a half hours. Webster was quoted as saying he had served the country by preemptively having “killed 17 Roman proconsuls” out of the speech to bring some sorely needed brevity.

Inauguration day, March 4, 1841, presented in Washington D.C, as cold, damp, and blustery. Harrison, to complete the vision of a healthy, vigorous man up to the job despite his advanced age, proceeded to deliver the 8,445 word, one hour and 40 minute speech directly facing the elements sans coat and top hat. Within days, he fell ill and was diagnosed as having pneumonia. The controversy regarding the inaugural speech as the death weapon contributing to his demise only one month later on April 4th 1841, remains in multiple official historical tomes. A more modern archival review now suggests Harrison may have essentially recovered from his pneumonia only to succumb to the quality of the WhiteHouse water supply fed by nearby fetid waters, resulting in dysentery and sepsis that ultimately ended his life and with it, the shortest administration in U.S. history. Regardless of cause, the Harrison Inauguration serves as a cautionary lesson to verbosity in speech writing, as poor Harrison pales next to the man who gave the shortest inauguration speech ever at 135 words, George Washington himself in 1793.

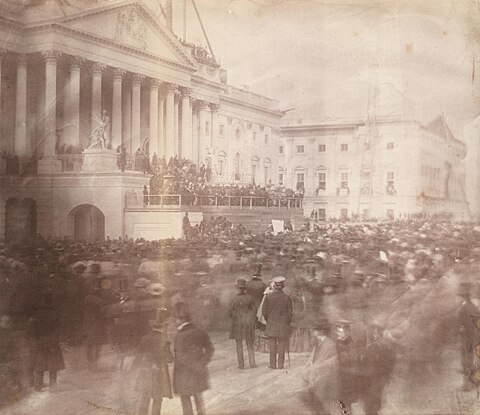

First Inauguration of the 16th President Abraham Lincoln – March 4th, 1861: It is hard to imagine higher levels of tension surrounding an inauguration then the one Abraham Lincoln had to confront upon his ascendancy to the Presidency. The previous President James Buchanan proved an abject failure at controlling the radical secessionist fever infecting South Carolina and other states of the Deep South, leading to the formal secession of seven southern states into a self declared Confederate States of America subsequent to Lincoln’s election in 1860. The election produced a radical split in the American electorate with Lincoln, the standard bearer of the newly formed Republican Party (founded on an anti-slavery doctrine) taking the populous northern states, the Democrat Party, irretrievably split between the Stephen Douglas Democrats espousing popular sovereignty (calamitously only securing Missouri and the District of Columbia), and the southern Democrats comprising the eventual Confederate states going to John Breckinridge, Buchanan’s Vice President. John Bell, representing the Constitutional Union Party, further carved off Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia. Lincoln came out with a minority of the vote (39.7%) but a majority of the Electoral College with 180 of 303.

The election of Lincoln fueled the rabid intensity of southern dissension, which grew to the point of formal secession. Federal forts in secessionist states were viewed by the radical secessionists as “occupying forces” requiring immediate evacuation, achieved with violence, if necessary. Lincoln, the great Western Unknown, had risen to national prominence with his spectacular Illinois legislature anti-slavery speech “A House Divided against itself, can not stand“, and through brilliant debates with Douglas for the Senate in Illinois in 1858, but was considered by much of the country utterly unprepared for the coming crisis. Lincoln, as elected leader now owned this crisis, and was presented with an impossible dilemma. Permit the unchallenged secession of the southern states and forever lose the concept of a United States, or challenge the secession forcibly by defending federal property and turn the insurrection violent beyond recovery.

As Lincoln approached Washington for the Inauguration, substantial evidence that there would be violent efforts made to stop his ascent to the Presidency abounded. He therefore secured confidential transport through Baltimore to avoid the assailants obtaining information or access that would assist them in carrying out their acts. This later would be framed as a “cowardly” Lincoln sneaking into Washington by disguise, but the truth was the dangerous threats were multiple, real and immediate.

With the country’s near complete unraveling framing his inauguration, Lincoln sought to the extent possible a conciliatory tone to his inauguration address, though indicating a firmness of resolve that would be foundational to his Presidency and leadership style. He denounced the secession process as antithetical to the principles of the Union and American style republicanism, but stated that his intent was not to interfere with slavery where it already existed, nor be the first to initiate violence in the face of the insurrection. His efforts to reach out have come down through history to us as American poetry of the highest order:

“I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angle of our nature.”

Lincoln’s beautiful words would not stop the cannonade of April 12, 1861 against Fort Sumter initiating the calamitous violence and desperate sacrifice of the next four years, the horror only assuaged finally through his martyrdom by an assassin’s bullet.

Inauguration of the 19th President Rutherford Hayes – March 5th, 1877 : For those seeing the chaos surrounding the 2020 election as a sui generis, with challenges regarding election integrity, alternate elector slates, or whether the Vice President has the power to overrule the desires of Senate President Pro Tempore in certifying the electors, the election of 1876 leaves the 2020 election controversy in the dust for all time.

The era proceeding out of the aftermath of the Civil War and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln was defined by the dominance of aggressive radical republicans in the legislature and the unfolding process of Reconstruction of the defeated southern states. The Constitution of the United States was amended with three revolutionary statutes – the 13th amendment abolishing slavery, the 14th securing birthright and naturalized citizenship, and the 15th assuring the right to vote for qualified male citizens, regardless of race. The devastated south was felt by the victorious north to require both a physical and moral reconstruction, and the ability for those states to restore responsibility over their internal affairs required that they show fealty to the constitution and its new amendments. Reconstruction money brought devoted civil servants and parasites to the South in equal measure. The initial post-war reality was the on-boarding of radical southern republicanism, reinforced by the newly powerful African-American populations at the ballot box and backed up and enforced by federal troops, bringing republican governments to power in the deep south. The southern states often felt humiliated and subservient, raising almost immediately the tinder for new rebellious reactions. The reemergence of violence, both real and threatened, made life extremely difficult for those newly freed southern populations to achieve their constitutional rights. Reactionary forces in the South began to develop nefarious means of “restoring” what they felt was the appropriate societal hierarchy by developing obstacles to African American citizens to engage their right to vote, serve in government and own property, the embryonic formation of what would eventually become the culture of “Jim Crow” laws.

States that successfully repelled republican governments over time, did so through the organization of the a white supremacist leaning Democrat party, sequentially elected across the southern states to dominate all levers in state power. By 1876, only three state governments in the south remained “unredeemed” – in other words, still in the hands of radical republican legislatures. The states were Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina.

Republicans had won every national election since 1860, but by 1876, a depression, the country’s exhaustion with the ongoing demands of Reconstruction, and President Grant’s determination to follow the Washington precedent and not seek a third term provided fresh opportunity for a national Democrat candidate to succeed. That Democrat candidate, the Governor of New York, Samuel Tilden, a reform minded democrat in the vein of the later President Grover Cleveland, looked poised to achieve the upset. The Republicans, tired by internecine fights, put forth a compromise candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes. A quiet, reserved man, Hayes was one of a line of Republicans born out of the Civil War experience. He was of the Ohio Volunteers, a five times wounded officer who rose to Major General during the war. He contrasted strongly with Tilden, who had not served. An exhausted country ripped by economic woes and ongoing havoc in the South, remained conflicted as to the best direction going forward. The election of November, 1876, seemed to initially indicate a new beginning. It appeared the next President was to be Samuel Tilden, having won a plural majority of 240,000 votes and 52.4% of votes cast, and a formidable electoral college lead of 184 to 166. The American election process however constitutionally required an electoral college majority. In 1876, this was 185 votes and Tilden was 1 vote short. Nineteen electoral votes across four states were in doubt. The challenges and recriminations of this epically close race began almost immediately.

Four states reported contested election ballots and had to work through post election dual elector slates as to who would represent them in the electoral college. The new western state, Oregon, determined to send a republican elector slate, leaving Tilden still one vote short and three outlying states to determine the winner. The three states were the infamous “unredeemed” states of Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina. The opinion of the republican legislatures and the democrat machines that had “tallied” the votes in these states were diametrically opposed as to how massive the combination of voter fraud and voter suppression had affected the outcome. Facing a constitutional crisis, the Congress came up with an unconstitutional solution. An”electoral commission” was formed to put distance between the federal republican congressional majorities and the appearance of “stealing” a presidential election from the apparent winner Tilden. The commission was comprised of 5 “elders” each from the House, Senate, and Supreme Court to adjudicate the dual elector slates, and began deliberation on January 29, 1877. The 15 member commission had a slight “finger on the scale” of 8 Republicans and 7 Democrats, and not surprisingly the vote on each of the outlying elector slates were 8 to 7 in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes. Due to fears of massive violence or realization of a multitude of assassination threats toward the candidates upon announcement of the winner, the Commission did not publicly announce its decision delivered to Congress on January 31, 1877, finding in favor of all contested elector slates, 19 in all, going to Rutherford B Hayes, making him the unofficial winner of the 1876 election over Tilden 185-184. Over the next month Congress, recognizing the appearance of a “soft coup” and looking to avoid tumult, formulated a confidential “backroom deal” between republican and democrat teams representing Hayes and Tilden respectively to award the election to Hayes at the cost of final removal of all federal troops from the South, specifically the “unredeemed” states. This electoral “solution” effectively ended the Reconstruction Era, thus subjecting the black minority populations of the south to an additional 90 years of “Jim Crow” torment and restriction of their constitutionally mandated citizen rights.

The electoral result was certified by Congress March 2nd, 1877, and Rutherford B Hayes was quietly sworn in privately on March 3rd, to circumvent possible violence affecting the official public inauguration on March 5th. On Inauguration day, Hayes spoke to his desire to lead a government that:

“guards the interests of both races carefully and equally. It must be a government which submits loyally and heartily to the Constitution and the laws- the laws of the nation and of the states themselves – accepting and obeying the whole Constitution as it is.”

Rutherford B. Hayes was a good man, but must have recognized the likelihood of his words being realized were as feasible as a Tilden Presidency, a relic of a Constitution that simply would never have a clear solution for every eventuality, or the level of moral purity that we, the people required for a more perfect union.

First Inauguration of the 32nd President Franklin Delano Roosevelt – March 4th, 1933: The circumstances surrounding the elevation of Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the Presidency were inextricably tied to the man and the times. The country had been one of the massive winners of the twin calamities of the early 2oth century – the Great War and the Spanish Flu epidemic that followed. The world war had destroyed the traditional powers in Europe and devastated its populations and industry, leaving it vulnerable to extremism and violence following the Russian Revolution and rise of Communism. The thirty millions that died in the war were almost immediately subsumed by the estimated 60 million that died worldwide as a consequence of the Spanish Flu pandemic, leaving most of Europe incapable of restoring its prewar elite economies. The United States, though impacted by the pandemic, had left the war the leading economy in the world. A series of free market limited government presidencies led to a massive, unabashed American economic expansion, the era collectively referred to as the Roaring Twenties. The hangover began with a collapse in the speculative markets worldwide but historically emblazoned by the sudden American stock market collapse of October, 1929. Although the speculative market disaster did not directly infer an economic decline, its psychological effect on an economy with too much supply and too little demand, banking strains, and progressive unemployment resulted in a progressive recession, bank closures, and ballooning unemployment without a safety net. President Hoover, a progressive republican who believed in the many potential capabilities in government, instituted many actions to attempt to reduce the pain for average Americans facing economic slowdown, including bank loan relief and massive injection of federal money into large job projects including roads, hospitals, waterways and dams. His poor understanding of the impact of modern media, however, particularly the new platform of radio, and his lack of ability to harness the platform, made him appear incoherent and insensitive in responding publicly to cascading events. The public lost confidence in Hoover despite his enormous administrative skills , and he was crushed in the 1932 presidential election by a candidate out of the New York Brahmin caste, a distant cousin of Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Franklin Roosevelt was destined to be a playboy backbench politician in the shadow of his famous relative until a life altering experience in 1921. Roosevelt was helpless in the face of a rare adult calamity when he was struck down by poliomyelitis, leaving him paralyzed and near suicidal. He was encouraged by his wife to seek care in Warm Springs, Georgia at an innovative program to restore some mobility in children struck down by the disease. He was forced to face his disease head-on with people completely out of his social circle and began to focus on the challenges average Americans faced every day. He discovered that radio functioned as a medium that could cloak his disability and, accentuated by the warm timbre of his broadcast voice, convey a sense of personal empathy surpassingly well to the mass audience.

He was the first politician to align opportunity with crisis, and made very little effort to support Hoover in the transition period before his inauguration The relative stabilization of the economy in 1932 began to slide again after the election. By the time of the inauguration, unemployment had slid to 25% and bank failures accelerated. Roosevelt was planning a massive governmental expansion as a mechanism to halt the slide and simultaneously secure a permanent, increased governmental role in the U.S. economy. The desperate American population was looking for a voice that could restore some semblance of confidence to the ever-increasing chaotic decline. For the next 12 years, it would be Franklin Roosevelt’s voice.

On March 4th,1933, Roosevelt faced the crisis head-on with a perfect synthesis of words, sounds, images and radio theater. The nation listened with intense attention, as a national media star was born and became the face of hope for the next 12 years through non-stop crisis and challenge;

“I am certain that my fellow Americans expect that on my induction into the Presidency I will address them with a candor and a decision which the present situation of our people impel. This is preeminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today. This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory. I am convinced that you will again give that support to leadership in these critical days.”

He spoke to his view of crisis management as equivalent to that in war – and a massive expansion of extra-constitutional executive power would be necessary to win such a war:

“It is to be hoped that the normal balance of executive and legislative authority may be wholly adequate to meet the unprecedented task before us. But it may be that an unprecedented demand and need for undelayed action may call for temporary departure from that normal balance of public procedure.

I am prepared under my constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken nation in the midst of a stricken world may require. These measures, or such other measures as the Congress may build out of its experience and wisdom, I shall seek, within my constitutional authority, to bring to speedy adoption.

But in the event that the Congress shall fail to take one of these two courses, and in the event that the national emergency is still critical, I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me. I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis—broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.”

It is difficult to underestimate the impression Roosevelt left upon his listeners that day and with each subsequent “fire side chat”. Despite the many failings of his executive overreach and creation of the permanent bureaucratic state that likely extended the depression, accompanying a subservience to traditional American isolationism that contributed to the U.S. passivity exploding the scope of later conflict, Roosevelt’s ability to relate directly to Americans over the heads of opponents brought an unprecedented four electoral victories and colossal mandates for his vision of a government led version of the American Dream.

Inauguration of the 35th President – John Fitzgerald Kennedy – January 20th, 1961: Its hard to describe a more forward looking inauguration then the one celebrated on January 20th, 1961. The Presidential election of 1960 had promoted a battle between to fresh faced, energetic veterans of World War II, whose respective ages were 43 and 46 on election day, nearly half the age of our current President Biden. The two candidates Nixon and Kennedy had more things in common then they had differences. Both were national figures politically accomplished in their 30s, Kennedy a U.S. Senator at 36 and Nixon Vice President of the United States at 39. Both looked to the future of an American economic colossus, were fervent anti-communists, confident international spokesmen of the superiority of the American vision, and free market anti-taxers. Where they differed most dramatically was in their skill in messaging on a new medium and its effect on the image associated with both politicians. Just like Franklin Roosevelt mastered the medium of radio to massive political advantage, John Kennedy created a new political force, the telegenic politician. Kennedy projected articulate dynamism, vigor, and downright sex-appeal in front of the camera. The Kennedy media packaging created a confident, knowing persona that covered up a relative lack of administrative experience and depth of intellect. The effect was profound. Those that heard the televised Presidential debate prior to the election on September 26, 1960, were convinced Kennedy had won the debating points. Those who heard it on the radio were convinced Nixon was the more informed, convincing leader. The tanned, smiling Kennedy appeared vigorous compared to the pale, wan stubbled Nixon, though it was Kennedy in real life who was braced and medicated against the ravages of previous injury and adrenal insufficiency, with Nixon contrastingly the steadfast, healthy alternative.

The election of 1960 was extremely close and may have turned upon some nefarious election activities in the state of Texas and Illinois. Nixon was relatively close to Kennedy in ideals and got along with him – as such, for the sake of the turmoil it would cause, he determined to not contest the results. Kennedy’s January 20th inaugural was theater on the scale of Roosevelt, this time on television. with his beautiful wife and children every bit as telegenic as he was. The Presidential family image completed the narrative that a royal Camelot was present in staid Washington. Kennedy took his inaugural speech and injected epinephrine into the image of a can-do country with limitless vision and opportunity:

“We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans–born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage–and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today at home and around the world.

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.

This much we pledge–and more.”

The country hardly had begun engage the vision Kennedy promoted, when he was struck down by an assassin’s bullet on November 22, 1963. The process martyred him, frozen in time as the young, mighty, and confident prophet of a better future. Subsequent decades and the eventual reporting of behind the scenes realities of his many foibles and personal flaws have done little to erase the image of what the nation saw as its own youthful vitality, only to have to face through Kennedy’s violent, premature demise, the harsh realities of an enforced more sober American Era middle age.

Second inauguration 47th President Donald J. Trump – January 20th, 2025: There are many interesting vignettes regarding other inaugurations – some uplifting, others disappointing, but the grand American experiment soldiers onward. On January 20th, 2025 we will again listen for direction from our elected executive, as he tries to frame the chaotic past eight years into a vision for the future that hopefully inspires. Trump descended into a darkness with his first inaugural speech under a cloud artificially birthed by his political foes. This time, he has emerged triumphant from a withering set of political attacks, legal warfare, and death defying assaults, to lead a nation again after losing the office, the first to achieve such a political rebirth since Grover Cleveland. Providence has made this nation pivotal, and therefore the leader representing it pivotal to defining a future of light and creativity, or darkness and conflict.

Every once in a while, the American Inauguration and the person it presents, stand bestride the Age.